Mesolithic Period

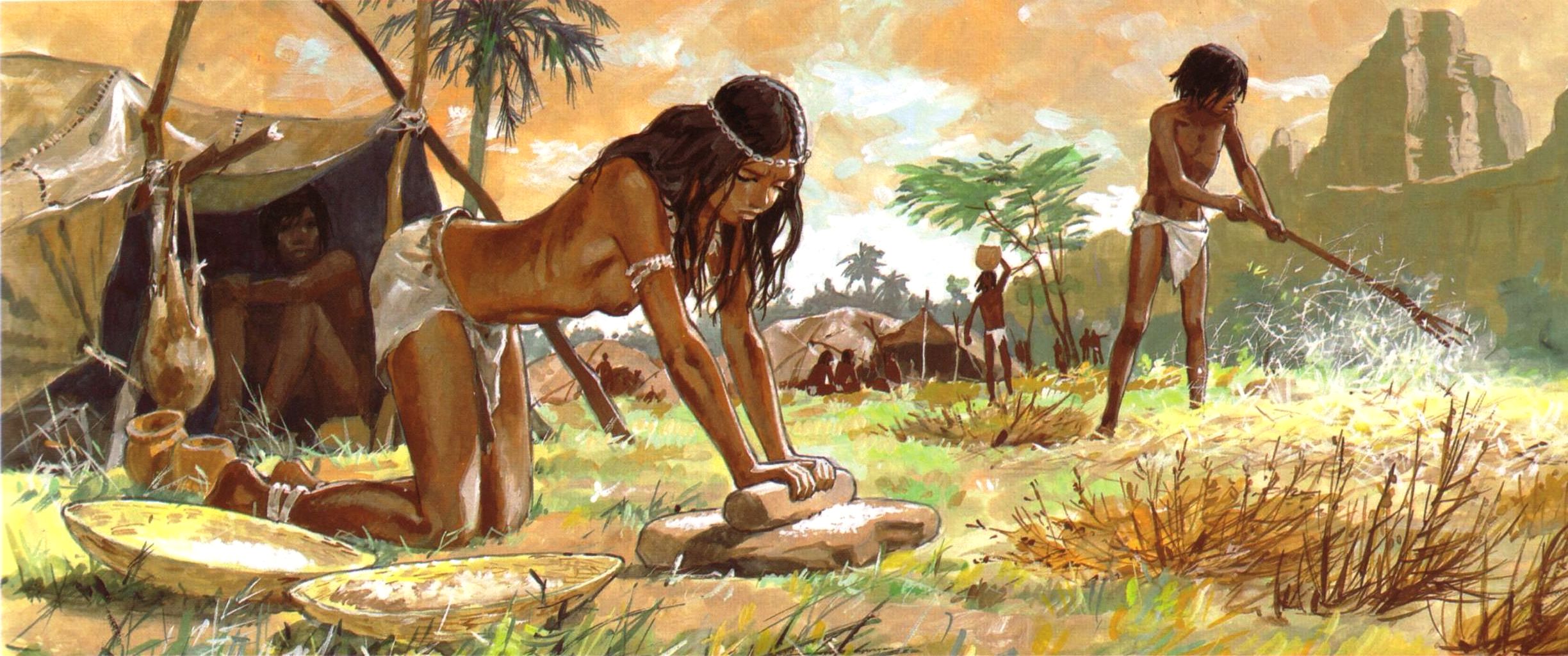

The Mesolithic Period extends between 12,000 and 8,000 BC. With the last of the Ice Age's retreat, the planet's climate gradually warmed; the rising abundance of plants and animals played a pivotal role in influencing humanoid subsistence strategies. Expanding forests, grasslands and waterways fostered a greater variety of food sources, necessitating adaptive responses. Adaptation was key; communities adjusted to the changing landscapes by diversifying their subsistence methods. The reliance on hunting, fishing and gathering persisted, but these activities became more specialised and efficient. To improve these practices, composite tools like harpoons and bows emerged as effective aids, increasing precision and effectiveness. Fishing techniques advanced with the use of specialised implements, improving access to aquatic resources. Gathering methods also benefited from tool innovations, enabling the collection and processing of a broader variety of edible plants.

Contents

An expanding range of tools and implements became available as materials and construction techniques improved. More durable and efficient instruments allowed for greater exploitation of available resources, reflecting an ongoing process of adaptation. Humanoid communities continually refined their means of interacting with the evolving environment, ensuring their survival in this transitional period. Shifts in settlement patterns produced sedentism, or the establishment of permanent settlements, as resources in some areas became more predictable. The extinction of many large animals pushed communities to adapt to diverse ecosystems — coastal, forested and arid environments — where survival depended on hunting smaller game and cultivating plants.

With a rise in small-scale societies came hierarchical structures for leadership and decision-making, largely overseen by groups of elders. Cultural and spiritual leadership was carried on by shamans, whose influence was enhanced by the rise of animism. Small, disconnected human communities were taking shape throughout the north temperate zone, in both the Old and New Worlds.

Human Culture

- Main Article: Humans in the Mesolithic-Neolithic Period

The Natufian culture of the Levant exhibited early signs of sedentism and early agriculture. With advances in art and symbolism, burial practices and the harvesting of wild cereals, the Natufian culture would eventually pave the way for the Neolithic way of life. Villages founded at Amman, Edessa and Gafsa in the 9th millennium made their mark as the world's oldest continuously occupied settlements.

In Mesopotamia, Mesolithic societies originated at Hassuna, Halaf and Ubaid, each characterised by early agricultural practices that would later define the region's development. The Jomon culture in Japan remained at a very early stage, though distinct pottery styles began to emerge as it transitioned toward the Neolithic.

In Anatolia, Göbekli Tepe suggests an early complex society engaging in ritual and monumental construction, predating agriculture but indicating organised labour and social stratification. The Kebaran culture, preceding the Natufian in the Levant, displayed early microlithic tool use and a semi-sedentary lifestyle. In China, groups along the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers began experimenting with millet and rice domestication, forming the precursors to later Neolithic cultures. The Saharan region, which was more hospitable during this period, supported hunter-gatherers who gradually adopted pastoralism, leading to what would become the early Saharan Neolithic.

In Europe, the Magdalenian and Azilian cultures, remnants of Upper Paleolithic traditions, adapted to post-glacial environments by refining hunting strategies and developing early symbolic expressions. Hunter-gatherer communities in the Americas, including those of Monte Verde in South America, showed signs of increasing social complexity, suggesting parallel developments alongside Old World Mesolithic cultures.

Northern Cave Peoples

At the same time, various new goblinish and orcish cultures began to establish themselves — goblins settling along the Ob River, while orcs clustered along watercourses and marshlands in the steppe regions to the south. Larger orcs, known as the haruchai, occupied parts of what is now Mongolia, adapting to the harsher terrain with a mix of nomadic and semi-sedentary practices. Bugbears, hobgoblins and ogres formed lasting cultures in the dense forests surrounding Lake Baykal, with their influence reaching as far north as the Arctic Ocean.

Further east, another goblinish race, the norkers, proliferated along the banks of the Lena River, developing distinct territorial claims in response to shifting environmental conditions. Meanwhile, the xvarts expanded even farther, reaching into northern Kamchatka and the Gulf of Okhotsk, adapting to the tundra and coastal environments with unique subsistence strategies suited to the cold, isolated regions.

Gnollish Culture

- Main Article: Gnollish History

In the Barents and Kara forest regions of present-day Bjarmaland, a gnollish culture known as the Gunda emerged. With wolf-like heads and large, powerful humanoid bodies, they are believed to have originated in the Kodar Mountains of Central Asia. Though smaller than giants, they shared many of their traits, particularly their resilience to extreme cold, much like frost giants. Brutally harsh winters had no effect on them, allowing them to thrive where other humanoid groups struggled. By the 9th millennium BC, a sparse but active gnollish presence stretched from the White Sea to Samoyadia, forming a network of semi-nomadic clans that adapted to the dense taiga and tundra.

Further east, a distant relation of gnolls, the flinds, established themselves along the shores of the Okhotsk Sea and the Pacific, shaping their own distinct culture in the coastal and subarctic environments.

Dwarven Culture

- Main Article: Dwarven History

As the glaciers along the Tien Shan and Altai ranges receded, dwarves migrated south and east into the lands of Croftsheim and Tuvath, where they remain to this day. These migrations followed the exposure of new highland valleys and river basins, allowing for more stable settlement. The rugged terrain suited their deep-rooted traditions of craftsmanship and stonework, laying the foundation for the enduring dwarven cultures of the region.

In the Khath basin, rudimentary agriculture had begun to take hold, marking an early shift toward food production that would later shape the region's development. The cultivation of hardy crops and the domestication of select animals likely complemented traditional hunting and gathering, allowing for the formation of more permanent settlements.

Gnomish Culture

- Main Article: Gnomish History

Between 10,000 and 9,000 BC, svirfneblin tribes began to emerge in the Dovrefjell, in what is now Scandinavia, establishing villages along the higher mountain slopes. Exposure to sunlight and a shift in diet brought rapid changes to their physiology, as they became slighter in build and less rough-hewn in appearance. Over generations, they began referring to themselves as "gnomes," a distinction that marked their adaptation to life beyond the deep places of the earth.

As they moved downward into the valleys, they encountered and cooperated with a human people known as the "Maglemosians," fostering a cultural exchange that influenced both groups. Through trade, shared knowledge and interwoven subsistence strategies, gnomish communities gradually integrated into the broader landscape. By the end of the Mesolithic, gnomes had spread steadily across Scandinavia, forming numerous settlements that would continue to shape the region's cultural and technological development.

Halflingen Culture

- Main Article: Halflingen History

From the start of the Mesolithic, a small-statured people descended from human stock established a sustainable culture along the northern edges of Eire, during a time when the region was still part of Britain's single landmass. Though unusually short compared to their human neighbors, the halflings distinguished themselves through remarkable ingenuity and adaptability. Their inventive nature allowed them to craft effective tools, refine survival techniques and create well-organised settlements that thrived despite their smaller numbers.

Living in peace, they gradually expanded their reach, founding settlements in what is now modern Cumberland, Stirling and Yorkshire. From these regions, their presence extended further into the fen country of Doggerland, where they developed a unique way of life adapted to the marshlands and shifting landscapes of the prehistoric North Sea basin.

See also,

Neolithic Period

Palaeolithic Period

World History