Infrastructure

Infrastructure describes the framework of civilisation that exists in a specific 20-mile hex map, based upon a region's population and the distribution of that population. The latter is affected by the geographical elevation of the hex as compared with other hexes in the same political region. Since infrastructure relies upon the willingness of a specific region to build public works within its control, the measure of a region's infrastructure is limited by the boundaries of that region. Therefore, a hex that's part of a dense political entity, with a very high infrastructure, can be directly adjacent to a wilderness when the two hexes are separated by a state border.

Infrastructure is used to determine the presence and nature of roads, what services are provided, cultural cohesion, education, manufacturing, wealth, agricultural development and much more. Zero infrastructure indicates the hex is wild, with no institutions or development of any kind. Backward areas have infrastructures between 1-7; mixed hinterland & rural parts, between 8-31; well-established agricultural zones, towns and small cities, between 32-99. Dense areas will have hundreds of infrastructure, with some very dense populated areas having infrastructures in the thousands.

Calculating Infrastructure

The system that calculates the infrastructure number is greatly affected by population, but does not describe a hex's population. A hex that is wholly rural can have half the infrastructure of an adjacent, densely packed urban hex — because the latter ensures that roads and installations are built in the former for general public use. Here follows a series of examples that explains how infrastructure is calculated and how it's affected by settlement location and topographic forms.

Population

Before infrastructure can be determined, we must know the FULL population of the region. This number can be arbitrarily assigned or calculated through whatever means the DM wishes. This full population needs to be subdivided among any number of towns or cities the DM cares to list in that given region.

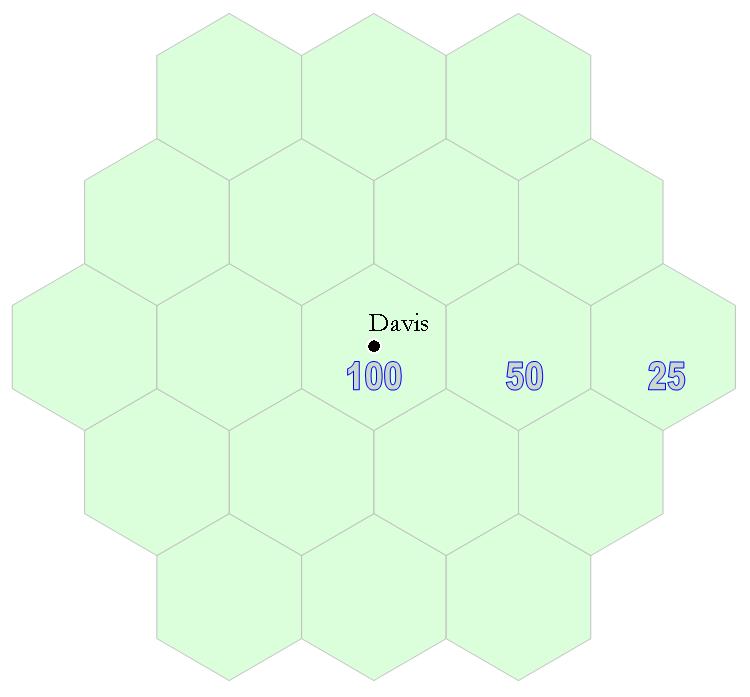

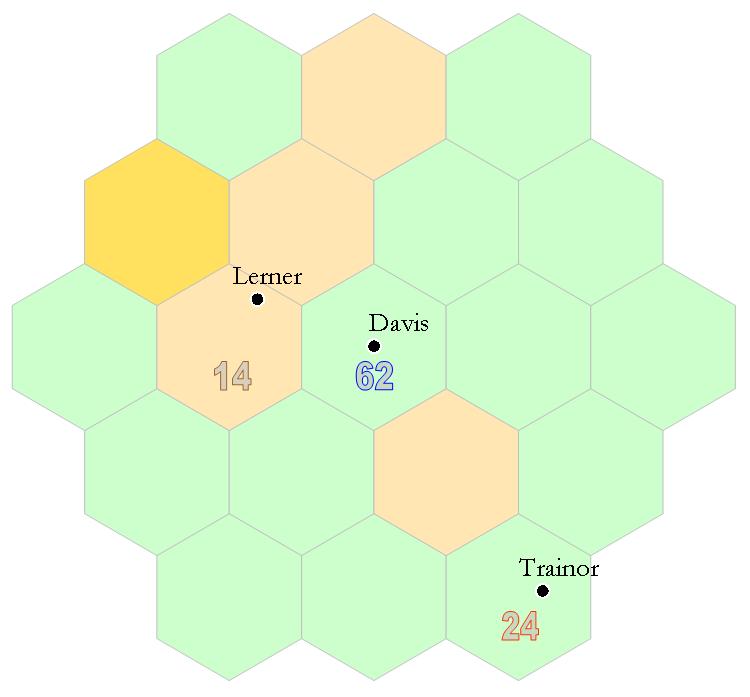

The first very simple example shows a region with one town, Davis. The whole region has a population of 34,600 persons, with all political decisions make within Davis; and therefore, all infrastructure is centered in and around Davis. The land represented is flat as a pancake, so there are no elevational obstructions to the building of roads. Each hex is 20 miles in diameter and 346 square miles. The total area is 8,650 sq. miles, nearly the size of New Jersey.

To obtain a single infrastructure number, we divide the total population by 346, the square miles per hex. This gives us a number of 100, which is the infrastructure of the hex that contains the only settlement Davis. All six hexes around the Davis hex have an infrastructure of 50, half of the Davis hex. And all hexes that are two away from Davis have an infrastructure of 25. If a third circle of hexes existed, they'd all have an infrastructure of 12 (fraction is ignored). This continues until a border is reached or until the infrastructure falls below 1, indicating a hex without infrastructure. In this case, the border is the edge of the 25 hexes, so there is no need to calculate the region's infrastructure beyond what's seen here.

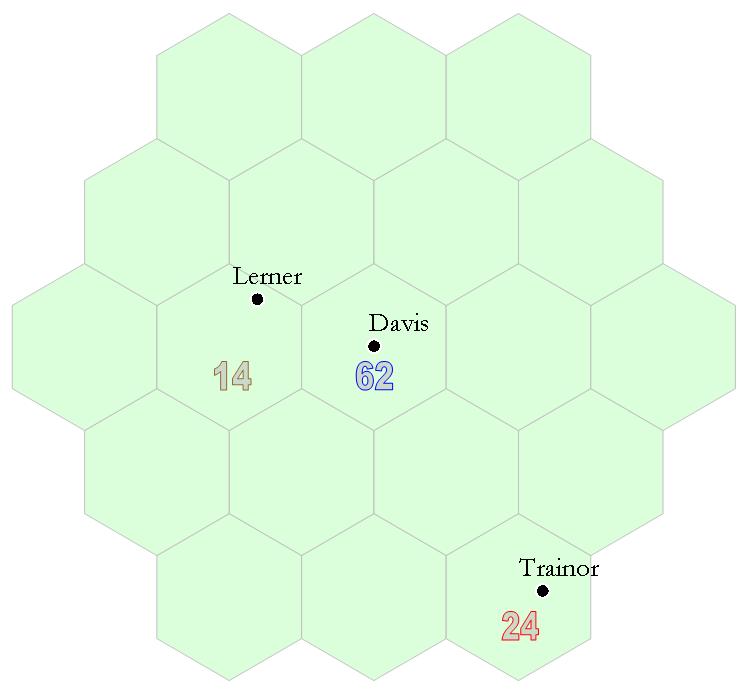

An example like this would hardly occur in the real world. Flat areas like this tend to be agricultural, with multiple settlements. Regions are also irregularly shaped; New Jersey is surrounded by water, for example. However, let's continue with the example, this time splitting the population between three centres. We'll retain the total infrastructure of 100 points.

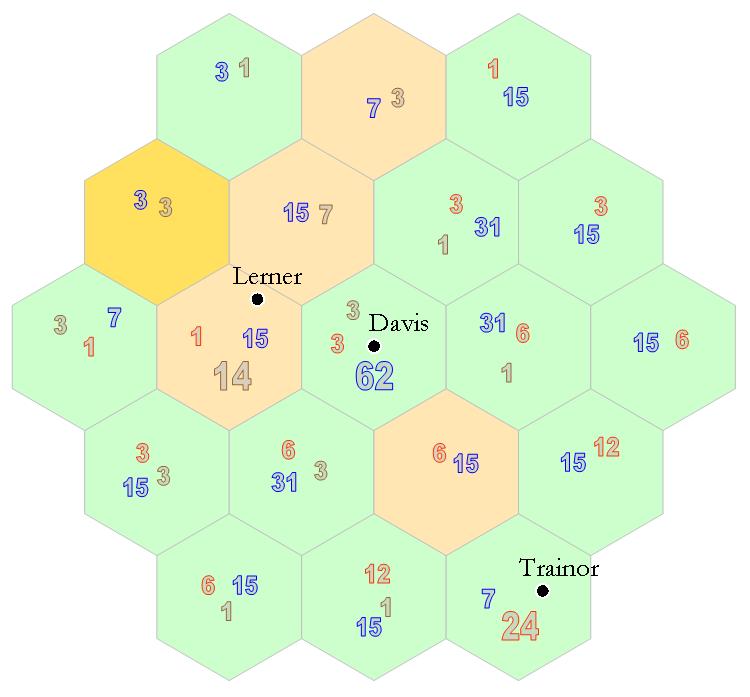

Multiple Centers

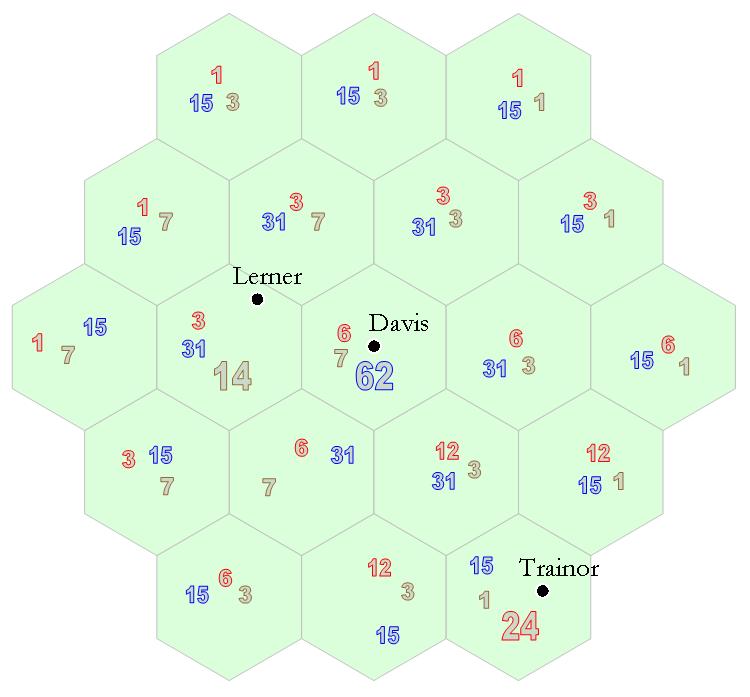

In this second example, Davis has an initial infrastructure of 62 (blue), Trainor has 24 (red) and Lerner has 14 (brown). Nothing else has changed. As before, the hexes surrounding Davis have half of 62; those surrounding Trainor have half of 24; and those surrounding Lerner have half of 14. Nothing outside the border of the region shown is affected by these centers, as they don't spend money or contribute to the infrastructure of other political regions (theoretically, they do, but for the sake of this system, we only concern ourselves with the effort they put to their own infrastructure). We can rough out the effect of these numbers throughout the map, which makes a mess: the origin of each center's influence on infrastucture can be traced by the colour of number being used.

Note how the infrastructure from Trainor affects to the totals for Lerner and Davis, and to different degrees. The total infrastructure for each area is the total gained from each expanded center. Let's add the numbers and see the results.

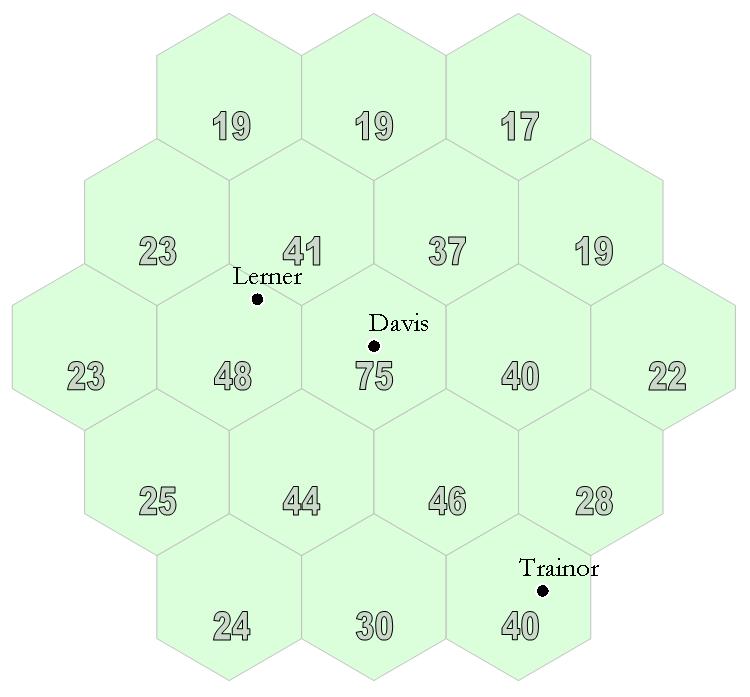

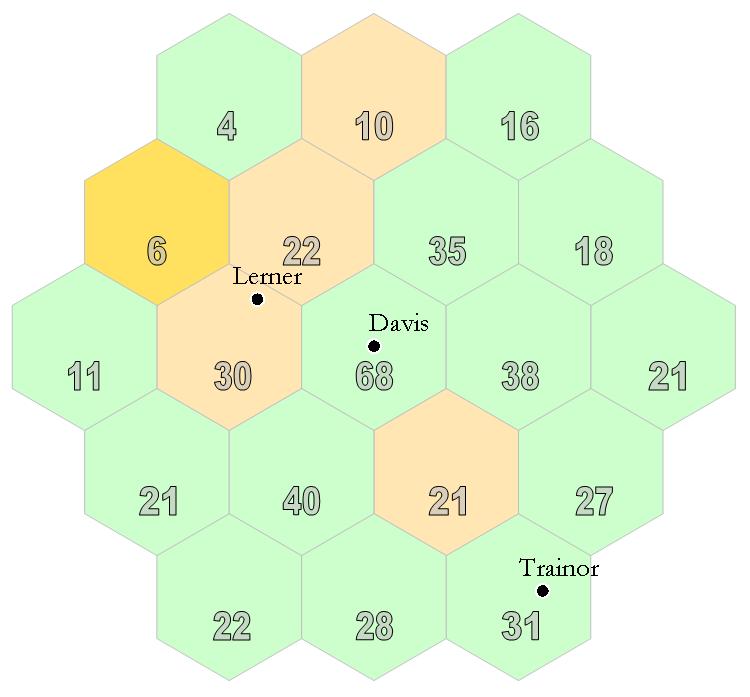

Elevation

As we can see, the results are less uniform. Even though Lerner is technically a smaller center than Trainor, it has more infrastructure because it is adjacent to Davis. However, it's clear the differences are subtle; in many ways, we're witnessing a more nuanced version of the first distribution out of Davis alone. Suppose, then, that we put in two groups of hills. In the map below, light orange indicates a hex that is between 400 and 799 above the plain; darker orange indicates a hex that is between 800 and 1199 feet higher. We'll put Lerner in a hex with low hills.

Here we start with the initial number of infrastructure points again. However, this time, whenever the colour between hexes changes, the division is twice what it was previously — this reflects the difficulty of extending infrastructure through jumbled topography. For example, Davis and Lerner are no longer on the same plain. Therefore, Davis' infrastructure is divided by four when extending it into Lerner's hex, and vice-versa. Let's produce a distribution again, as we did before.

Now, Lerner contributes hardly anything to the region; it's influence doesn't reach Trainor at all, nor the eastern line of hexes. Trainor barely adds 1 infrastructure to Lerner's hex. The upper left corner, behind the hills, gets even less than the high hills above it. Let's add the numbers and see the final totals.

We see a more diverse distribution here than previously. Every 400-foot difference increases the exponent (2x) that applies while moving outward from the originating center. High changes in elevation can effect a "wall" of wilderness, even when a very large city is located at it's base. Additionally, more cities, with greater deviation in base infrastructure than what's shown here, coupled with less homogenic shapes, provides further individualism among different regions. Very large regions may have islands of infrastructure scattered between wild expanses.

Other brakes against the spread of infrastructure from one hex to another includes desert hexes, wasteland, vast marshy areas and large bodies of water. Whenever possible, the mapmaker should strive to perceive a population center building infrastructure outward in a cohesive and logical fashion.

See Also,

Hex Group

Mapmaking

Settlements

Sheet Maps

Travel