Egyptian History

Egyptian History centers on the Nile Valley, which remained uninhabited by humans until after the last Ice Age. As the once-verdant Sahara plateau underwent desertification, both people and animals were forced to migrate — some toward the Mediterranean, others eastward to the Nile. During the Palaeolithic, human communities occupied the cliffs overlooking the valley. In the Neolithic, early agriculturalists moved down to the valley floor, where they cultivated crops in the fertile soil left by the Nile's seasonal floods. This annual inundation enriched the land with nutrient-rich silt, making sustained agriculture possible and shaping the rhythms of Egyptian life and culture.

Contents

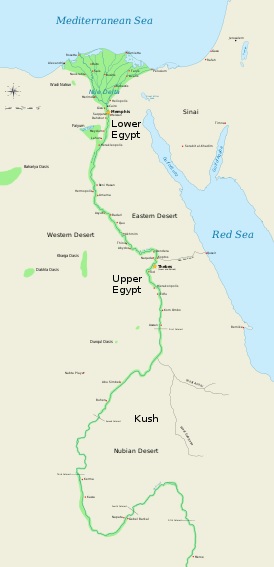

By this time, as many as forty agricultural communities had formed along the Nile north of the First Cataract, strung like beads along the river’s fertile edge. By around 5000 BC, these settlements had coalesced into two distinct kingdoms: one in the delta region, known as Lower Egypt, and the other in the Nile Valley, or Upper Egypt. This period marked the emergence of key cultural, social and technological patterns that would come to define Ancient Egyptian civilisation. After centuries of conflict during the Chalcolithic period, the two kingdoms were unified under King Menes, also known as Narmer, who founded his capital at Memphis in the northern Nile Valley. This unification marked the beginning of Egypt’s 1st Dynasty.

Early Dynastic Period

Lasting from 3200 to 2800 BC, the Early Dynastic marks the emergence of the pharaonic civilisation. During this era, the rulers of Egypt established a centralised state, consolidating the authority of the pharaoh while building a bureaucratic framework to oversee the administration of the realm and its regional officials. Hieroglyphic writing developed rapidly, and the pharaohs began constructing elaborate royal tombs as expressions of their divine status. Agriculture remained the foundation of the economy, supporting the growth of trade and craftsmanship.

Religion was central to society. The pharaoh was regarded as a divine intermediary, receiving messages directly from the Gods — a belief mirrored in contemporary Mesopotamia. Temples multiplied, and religious practice evolved in response to a polytheistic awakening. Yet, this divine order clashed with the emerging ambitions of mortals, resulting in unrest that ultimately laid the groundwork for the Old Kingdom.

Artistic conventions began to take form, laying the foundation for Egypt's distinctive visual language in sculpture, relief and statuary. These conventions reflected the hierarchical structure of society, with proportions and poses reinforcing status and divine authority. Monumental architecture was still in its infancy, but early mastabas — bench-shaped tombs — hinted at the funerary sophistication that would define later dynasties. Trade routes expanded both within and beyond the Nile Valley, reaching into the Sinai for copper and into Nubia for gold, while contact with the Levant introduced new materials and ideas. The role of the palace became increasingly ceremonial as the bureaucratic class took on administrative burdens, marking the beginning of a complex relationship between the image of the pharaoh and the machinery of the state.

Old Kingdom

This lasted from 2780 to 2270 BC, spanning the 3rd to 6th Dynasties. The capital remained at Memphis. This era includes the most renowned pyramid builders of the 4th Dynasty. Zoser (Djoser) of the 3rd Dynasty commissioned the step pyramid at Saqqara, while Cheops (Khufu), Chephren (Kha-ef-Re) and Mycerinos (Men-kau-Re) of the 4th Dynasty built the great pyramids that still stand at Gizeh. These structures were not only symbolic expressions of royal authority — they also demonstrate the immense wealth and power wielded by 4th Dynasty rulers. The vast resources poured into constructing these royal burial chambers ultimately contributed to the gradual weakening of the state, a decline that became increasingly evident through the 5th and 6th Dynasties.

Advanced construction techniques reached new levels of refinement, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of geometry, material handling and architectural balance. Quarrying systems enabled the mass extraction of limestone from Tura and granite from Aswan, used not only for temples and monuments but for the smooth, white casing stones that still covered the pyramids at Gizeh, which gleamed in the sun as brilliant, flawless monuments to royal authority. These were surrounded by expansive funerary complexes, causeways, mortuary temples, storage chambers and administrative buildings, forming the core of a living religious and political landscape. Irrigation systems using canals and dikes were engineered to manage the seasonal flow of the Nile, stabilising agriculture and population growth. Artisans refined bas-relief into a narrative form, developed precise techniques of proportion and scale, and produced detailed statuary that reinforced social and divine hierarchies. Surveying methods allowed accurate land demarcation even after the disruption of annual floods, supporting taxation, inheritance and central oversight.

The Old Kingdom collapsed after 2300 BC, as internal coherence unraveled under the weight of decentralised wealth and power. With regional governors acting autonomously and central leadership diminished, Egypt entered a prolonged period of instability and fractured rule. The 7th and 8th Dynasties emerged during this time, but held little effective power, and the country descended into disunity and feudal rivalry that endured for nearly four centuries.

Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom lasted from 2143 to 1790 BC, encompassing the 9th to 12th Dynasties. Ruling from Thebes, the early dynasties of this period labored toward the restoration of central authority after centuries of fragmentation. Progress was gradual at first, but by the 12th Dynasty, under the leadership of Amenemhet I and his son Sesotris I, Egypt was once again unified and internally stable. These kings curtailed the independence of regional nobles, replacing them with appointed governors loyal to the crown, thereby reasserting pharaonic control over the provinces. Major building projects were commissioned, including new temples and pyramids at El-Lisht and early work at Karnak, marking a revival of state-sponsored architecture and the reestablishment of centralised religious power.

Egyptian influence expanded southward through military and commercial expeditions into Nubia, where fortresses were constructed above the First Cataract to secure trade routes and mineral wealth. These campaigns also served to project Egyptian authority beyond its traditional borders. Shipbuilding techniques improved significantly, with the development of more durable and navigable river craft, enabling more efficient transport along the Nile and into foreign waters. This facilitated an increase in trade not only with Nubia, but with regions across the Red Sea and into the Levant. Egyptian merchants, for the first time, began appearing in substantial numbers beyond their native lands, and exotic goods such as incense, ivory, timber and lapis lazuli became more common in Egyptian markets.

In art and architecture, the Middle Kingdom produced significant advancements. Statues and reliefs achieved greater realism in the depiction of human features, moving away from the formal rigidity of earlier periods. Temples became more complex, incorporating elements like colonnades, massive pylon gateways and stylised papyrus columns. The casting of bronze and the alloying of metals saw technical improvements, supporting both functional tools and ornamental objects. Pottery became more refined and textile production grew in quality and quantity, suggesting a thriving artisan class supported by a revitalised economy.

Sesotris III (1887–1849 BC) was among the most powerful rulers of the period, leading campaigns deep into Syria and establishing military outposts along the eastern frontier in what became known as the Ways of Horus. These fortified checkpoints served not only military purposes but also as customs stations for trade and points of administrative control. His reign marks the height of Middle Kingdom power and territorial ambition.

Yet the Middle Kingdom's stability began to erode in the decades following Sesotris III. Corruption crept back into the bureaucracy, and agricultural output declined, weakening the state's financial base. Internal disputes over succession fractured the royal line, undermining the central government's ability to respond to emerging threats. During this time, foreign populations, notably the Hyksos, began to infiltrate the eastern Delta. Over time, their influence grew, until they succeeded in dominating much of Lower Egypt. This ushered in the Second Intermediate Period, a span of roughly 150 years marked by disunity, foreign rule in the north, and a diminished role for Egypt on the international stage.

New Kingdom

Lasting from 1555 to 1090 BC, encompassing the 17th to 20th Dynasties. By 1600, a resurgent Egyptian movement had successfully driven out the Hyksos, the foreign rulers who had controlled parts of the Delta during the Second Intermediate Period. Sekhem-Re, a capable military leader and the first pharaoh of the 17th Dynasty, dismantled the remnants of the entrenched nobility and redistributed their estates, restoring land and power to the crown. With unity re-established, Egypt entered a period of renewed strength, governed through a complex, professional bureaucracy headquartered at Thebes. Under the rulers of the 18th Dynasty, particularly figures like Thutmose III and Amenhotep III, Egypt expanded aggressively into the Levant and Nubia, becoming the dominant military and diplomatic force in the Near East. Tribute and spoils from these campaigns enriched the temples and treasuries of the Nile Valley.

Egyptian warfare underwent a transformation with the adoption of new military technologies, including composite bows with greater range and power, and horse-drawn chariots that allowed for greater mobility on the battlefield. These advances gave Egypt a decisive advantage in both offensive campaigns and the defense of its borders. Monumental architecture flourished as never before. At Karnak, immense hypostyle halls were constructed with forest-like colonnades, and the temple complex reached its greatest scale and grandeur. New shrines and ceremonial avenues were built at Luxor, and vast royal mortuary temples lined the western bank of the Nile, including the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri. These projects were not only religious expressions but assertions of imperial ideology, linking pharaohs with the divine order and projecting power to the farthest edges of the realm.

Technological and artistic innovation marked the period. The Egyptians refined the art of glassmaking, mastering the techniques of glassblowing and coloration that produced beads, vessels, and inlays of striking clarity and brilliance. Advances in medicine included surgical practices, diagnostic texts, and pharmaceutical recipes, while the fields of mathematics and astronomy became more systematised, supporting architecture, taxation, and ritual calendars. Magical practices were codified alongside scientific knowledge, often working in tandem within the religious and healing professions. Shipbuilding and navigation expanded Egypt’s ability to trade and project influence, not only up and down the Nile, but across the Red Sea and into the eastern Mediterranean, where Egyptian goods and culture became fixtures in foreign courts and markets.

Conquests

Amenhotep I (1555–1540 BC) was the first Egyptian ruler to push beyond the traditional boundaries of the empire and reach the Euphrates, initiating the expansionist policies that would define the New Kingdom. His campaigns laid the foundation for later military successes, but it was under Hatshepsut, regent and later co-ruler with Thutmose III, that Egypt stabilized internally and projected economic and diplomatic influence abroad, notably through expeditions to Punt and the reassertion of authority in Nubia. While Hatshepsut’s reign was marked more by trade and temple building than warfare, it was her stepson and successor, Thutmose III, who emerged as Egypt’s most accomplished military commander.

Over the course of nearly two decades, Thutmose III led annual campaigns deep into the Levant, extending Egyptian rule from the Sinai to the banks of the Euphrates. His decisive victory at Megiddo secured Egyptian dominance over Canaanite and Syrian vassal states, and his success at Kadesh reinforced that supremacy. These victories established Egypt as a true imperial power and brought the rich city-states of the Near East under Egyptian influence. Thutmose III’s long war with the Mitanni weakened their hold over northern Syria, and his military brilliance earned Egypt the deference of distant powers, including the rising Hittites in Anatolia, who at the time remained diplomatically cautious.

His gains were preserved and consolidated by his successors, Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV. Thutmose IV reversed Egypt’s earlier hostility toward the Mitanni, forging an alliance against the expanding Hittite threat. He sealed this relationship by marrying a Mitanni princess, inaugurating a tradition of diplomatic marriages that would become central to Egyptian foreign policy.

Amenhotep III (1411–1375 BC), known to the Greeks as Memnon, presided over a period of exceptional prosperity and global prestige. His rule was marked less by conquest than by careful diplomacy, building alliances through marriage and exchange of gifts with Babylon, Assyria, Mitanni, and the Hittites. Egypt’s reputation was so formidable that foreign kings vied for the favor of the pharaoh, whose court became the cultural and political center of the Near East. Amenhotep’s reign is remembered as a golden age, characterized by grandiose building projects, flourishing arts, and an international order dominated by Egyptian prestige rather than force.

Later in the New Kingdom, Egypt would again be drawn into conflict with the Hittites, particularly under Seti I and Ramesses II. These wars culminated in the famous Battle of Kadesh (c. 1274 BC), one of the earliest battles in recorded history for which tactical formations are known. Though the outcome was indecisive, Ramesses II used it as propaganda to depict himself as victorious, and a peace treaty—the earliest known surviving international accord—was eventually signed between Egypt and the Hittite Empire. This ushered in a period of relative stability between the two powers, but it marked the end of Egyptian expansion and the beginning of a more defensive posture in foreign affairs.

Decline

After the death of Amenhotep III, the accession of his son, Amenhotep IV, marked the beginning of a sharp and destabilising decline. Abandoning the diplomatic mastery and imperial responsibilities of his predecessors, Amenhotep IV adopted the name Akhenaten and initiated a sweeping religious revolution. Centering worship on the sun disc Aten, he rejected the traditional pantheon and priesthoods, particularly the powerful cult of Amun. His focus shifted from empire to ideology, and he moved the royal court to a new, isolated capital at Akhetaten (modern Amarna). The military and diplomatic networks so carefully maintained under earlier rulers began to unravel. The Mitanni kingdom, long a buffer against Hittite expansion, collapsed in the absence of Egyptian support. Hittite forces advanced, scattering Egypt’s allies in Syria and threatening the empire’s northern holdings. Akhenaten’s religious vision left Egypt weakened, spiritually divided, and politically exposed.

Upon his death, he was succeeded by the child pharaoh Tutankhamun, who restored the old gods in name but was powerless to recover Egypt’s crumbling influence abroad. Surrounded by court advisors and regents, Tutankhamun presided over a kingdom increasingly encircled by hostile powers. The brief reigns that followed—including those of Ay and Horemheb—saw a scramble to reclaim order. Horemheb, a former general, proved effective in halting the state’s disintegration. As the last ruler of the 18th Dynasty, he initiated administrative and legal reforms, strengthened the military, and began reasserting Egypt’s sovereignty, though the empire remained diminished.

Horemheb named as his successor Ramses I, a fellow soldier, who founded the 19th Dynasty. Ramses I reigned only briefly, but his son, Seti I (1290–1279 BC), brought renewed vigor to Egypt’s foreign policy. He campaigned in Syria and Palestine, checked Hittite influence, and worked to restore Egypt’s northern frontier. Seti’s efforts enabled his son, Ramses II (1292–1225 BC), to assume command of a reinvigorated state. Ramses II, remembered for his extensive building projects and commanding presence, assembled one of Egypt’s largest armies and marched north to confront the Hittites. The ensuing Battle of Kadesh (1274 BC) became a legendary confrontation—the earliest battle in history with surviving tactical records. Though the battle ended in a stalemate, Ramses II leveraged it into a political victory, portraying himself as triumphant in monumental inscriptions. Ultimately, he negotiated a peace treaty in 1266 BC with the Hittites, securing Egypt’s southern claims in Syria and marking the first known international peace agreement in recorded history.

By the close of the 13th century BC, new threats emerged that would prove even more destabilising. Raiders from the sea—collectively known as the Sea Peoples, including Philistines and related groups—began attacking the Nile Delta. At the same time, Libyan tribes advanced from the west, placing pressure on Egypt’s borders. Though the Hittites were now allied with Egypt, they themselves were under siege from waves of migrating tribes and internal collapse. Ramses III (1198–1167 BC), the second pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty, mounted a successful defense of Egypt’s frontiers, defeating the Sea Peoples in a series of land and naval engagements and temporarily securing the Delta. He also constructed monumental temples, such as Medinet Habu, to commemorate his victories.

Nonetheless, the cost of these wars drained Egypt’s resources. Prolonged military mobilization sapped the economy, and administrative corruption deepened. Agriculture declined under the weight of poor harvests and mismanagement. The bureaucratic structure faltered, and the loyalty of regional governors weakened. By the end of the 12th century BC, Egypt’s international influence had evaporated. The empire was lost, and though Egypt remained unified in name, its power had collapsed, ushering in a period of internal fragmentation and vulnerability.

See also,

Bronze Age

Ptolemaic Egypt

World History