Bronze Age

The Bronze Age extends between 3200 and 1200 BC, marking the transition from prehistory to recorded civilisation and culminating in the widespread collapse of societies across the eastern Mediterranean. This era saw significant advancements in bronze metallurgy, leading to improved tools and weapons for farming, construction and warfare. Developments in pottery and ceramics enhanced storage, cooking and trade, while the use of wheeled vehicles, including carts and chariots, transformed transportation and military tactics. The emergence of writing systems enabled the documentation of laws, administrative records, religious texts and historical accounts, facilitating the growth of bureaucratic governance.

Contents

Textile production expanded as weaving techniques became more sophisticated, supporting the development of trade networks that connected distant regions. Metalworking extended beyond bronze to include iron, silver and gold, allowing for the creation of intricate jewelry, finely crafted ornaments and decorative artifacts that held cultural and economic value. These advancements laid the foundation for complex societies, fostering urban centers, specialised craftsmanship and expansive trade routes that shaped the civilisations of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Anatolia and the Aegean.

Human history during the Bronze Age saw the rise of ancient Egypt, Sumer and Akkad, the Hittites, Mycenaean Greece, the Indus Valley culture and the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties in China. Alongside these human civilisations, the gnomish Vepsian empire flourished in the vast northern forests of Europe, controlling trade and resources in the region. From the west, elves appeared and established the Colyan culture, leaving an enduring mark on history through their artistry, governance and arcane traditions. Meanwhile, in the east, the hobgoblins of the Yaxjasso empire rose to power, expanding their dominion across much of Siberia through military conquest and the establishment of fortified strongholds.

Countless other civilisations also emerged during this era, shaping the cultural and political landscape of the world. Many of these societies have faded into obscurity, their histories lost or shrouded in myth, leaving only fragments of knowledge for scholars to uncover.

Egypt

- Main Article: Egyptian History

The era comprised the Early Dynastic period, followed by the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms, the last of which ended in 1090 BC.

The Old Kingdom (c.2780–2270 BC) marked the height of Egypt's wealth and power, centered in Memphis, on the Upper Nile. This period saw the construction of the Pyramids at Gizeh, the flourishing of agriculture and the occupation of Sinai and its copper mines. However, the kingdom's vast expenditures on monumental architecture and royal projects placed a heavy burden on the economy. Over time, political instability and financial strain led to a period of fragmentation and decline.

The Middle Kingdom (c.2143–1790 BC) restored Egypt's unity with its center at Thebes. The pharaohs expanded southward beyond the First Cataract and waged military campaigns into Syria. This period is known for its classical artistic and literary achievements, as well as the establishment of long-distance trade with the Fertile Crescent and the Red Sea regions. However, the kingdom fell into turmoil following the invasion of the Hyksos from Syria, leading to a breakdown of central authority.

The New Kingdom (c.1555–1090 BC) saw Egypt drive out the Hyksos and reassert its dominance, becoming the most formidable military power in the region. The pharaohs extended their control over Syria and clashed with the Hittites, creating an empire at the height of its influence. However, the cost of maintaining distant territories proved unsustainable. The kingdom's decline accelerated as Sea Raiders attacked the Delta and Libyans pressed in from the west. By the end of the 12th century BC, relentless warfare and financial strain led to the complete collapse of the Egyptian state.

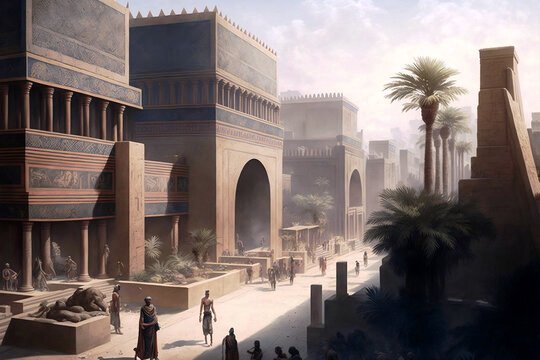

Mesopotamia

- Main Article: Mesopotamian History

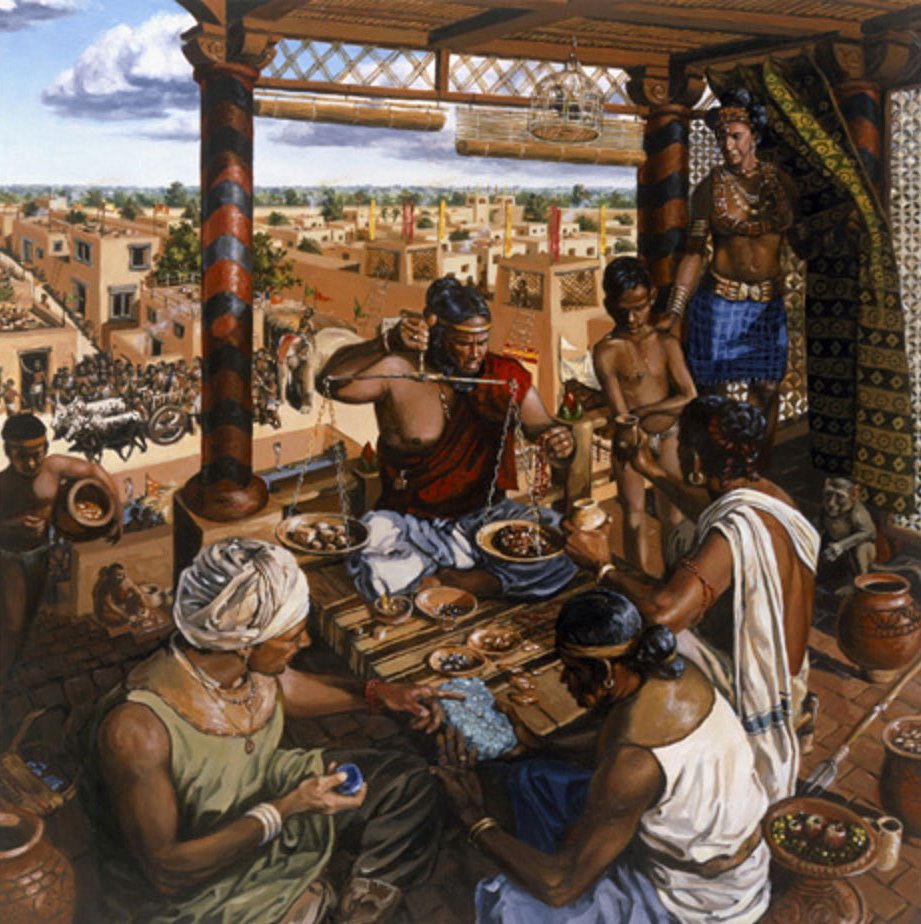

The Euphrates-Tigris valleys were home to numerous Sumerian city-states, with Uruk as the largest and most influential. Trade flourished among cities such as Ur and Lagash, but so too did warfare. No single city could establish lasting dominance until the rise of Akkad. In the 24th century BC, Sargon of Akkad led military campaigns that forged an empire unparalleled in the region. However, internal strife and instability led to Akkad's decline, allowing other city-states to contest its former power. Ur, Isin and Larsa each held dominance for a time, but these struggles gradually weakened Sumerian influence. Meanwhile, Amorite peoples from the west settled in Mesopotamia, integrating into its political and cultural landscape.

In the 18th century BC, Hammurabi ascended as ruler of Babylon, transforming his city-state into an empire. As Babylonian culture flourished, Sumerian identity faded, absorbed into the new power structure. However, after only 150 years, Babylon's unity began to fracture. A combination of drought, war and pestilence devastated the region. In 1595 BC, the Hittites sacked Babylon, while the Hurrians surged south from the highlands, establishing the Mitanni Kingdom in the lands of Syria and the upper Euphrates. Positioned between Babylonia, Egypt and the Hittite Empire, Mitanni became a key power in the region.

The last rulers of Babylon's founding dynasty fell in the 16th century BC, opening the way for the Kassites to take control of the southern plains. Their rule lasted for centuries, but as their power waned in the 12th century BC, Mesopotamia once again fell into political turmoil.

Surrounding Cultures of Mesopotamia

Elamites

Dating back to the 3rd millennium BC, the Elamites established themselves in the region of Elam, encompassing the southern Persian plateau. Their civilisation developed independently from Sumer and Akkad, forming a network of city-states, with Susa as its most prominent center. Despite their autonomy, the Elamites engaged in trade, diplomacy and military conflicts with their Mesopotamian neighbours. Over time, Elamite culture reflected increasing Mesopotamian influences, particularly in governance, religion and artistic expression.

Elam remained a formidable power as larger empires emerged and declined around it. By the 16th century BC, Elam experienced a period of expansion and regional prominence, solidifying its influence over neighboring territories. The kingdom continued to grow in strength, reaching its height in the 12th century BC under the Shutrukid dynasty. This ruling family led Elam during the Late Bronze Age, exerting control over parts of Mesopotamia and leaving a lasting mark on regional history. Shutrukid rulers conducted successful campaigns against Babylon, carrying off monuments such as the famous Stele of Hammurabi to Susa as a symbol of their dominance.

Although Elamite power fluctuated over the centuries, their resilience allowed them to remain a key player in the geopolitics of the ancient Near East. Their ability to adapt to shifting political landscapes ensured their survival, even as larger empires came and went.

Hittite Culture

The Hittites were a feudal state of central Anatolia that emerged around the 17th century BC. Their chief city, Hattusa, was founded around this time. The exact origins of the Hittites remain uncertain, but it is clear they migrated into Anatolia from elsewhere. Over time, they adopted and adapted elements of the existing cultures in the region, developing their own distinct religious beliefs, artistic traditions and administrative systems. At the head of their society stood a hereditary ruler, the Great King.

One of their most significant advancements was an early mastery of ironworking, which provided them with a major military advantage. They were among the first civilisations to use iron extensively, a metal far stronger than bronze. The Hittites were also skilled charioteers and made innovations in chariot design. Combined with their advanced fortification techniques, these developments made them a formidable force, particularly against the Egyptians and later the Mitanni. Adopting cuneiform from the Babylonians, the Hittites became adept diplomats and negotiators.

Between the late 16th and early 15th centuries BC, they fought a series of wars with the Mitanni. Under Suppiluliuma I in the 14th century BC, the Hittites expanded aggressively, conquering large parts of Anatolia and northern Syria, often clashing with Egypt. After the Treaty of Kadesh (1274 BC), peace was established. However, in the following centuries, the Hittites faced repeated raids by the Sea Peoples, along with devastating droughts and internal conflicts that weakened their trade networks. The destruction of Hattusa (c.1180 BC), likely at the hands of the Assyrians, marked the end of Hittite power. Their lands were later settled by the Phrygians and Lydians.

Mitanni Culture

The Mitanni people, also known as the Hurrians, are believed to have migrated into northern Mesopotamia around the 15th century BC. Establishing themselves in what is now modern-day Syria and northern Iraq, they occupied a vital strategic position along trade routes connecting Kassite Babylonia, Anatolia and the Levant. This location allowed them to exert influence over the movement of goods, particularly metals, textiles and horses, which were highly prized in warfare. Their kingdom, with its capital at Washukanni, flourished as an intermediary power, balancing diplomatic and military relationships with the surrounding empires.

At its height, between the 15th and 14th centuries BC, Mitanni controlled much of northern Mesopotamia, forming alliances with Egypt and competing with the Hittites and Assyrians for dominance. Mitanni rulers were known for their expertise in horsemanship and chariot warfare, and their influence extended into military tactics across the region. However, internal struggles and external pressures weakened the kingdom. Conflicts with the expanding Hittite Empire led to a decline, and by the 13th century BC, Mitanni was caught between the growing might of the Hittites and the resurgence of Assyria. Eventually, their territory was absorbed into these larger states, leaving behind a cultural legacy but failing to achieve the lasting influence of their more powerful neighbours.

this has been rewritten to this point

Levant

- Main Article: Hebraic History

At the beginning of the 3rd millenium B.C. the kings of the early dynasties of Egypt were sending expeditions northward to conquer the land of Canaan in order to control its commerce and obtain timber, metals and other raw materials. Fortified towns were built, notably the walled city of Jerusalem. Through much of the Bronze Age, this region was subjected to the rule of outsiders; but in the 14th century BC, a collection of Hebrew clans entered and settled here. As the Hittites and Egyptians began to collapse, these established a small culture from Galilee to the Jordan river, whose religious and cultural views would have enormous influence in the Late Bronze Age.

Hellenistic Cultures

Minoans

A sophisticated and prosperous society that flourished on the island of Crete in the Aegean Sea, roughly from 2700 to 1450 BC. Emerging from early settlements and agricultural communities, a complex culture arose with the construction of the first palace complexes in the late 3rd millennium BC. Trade networks expanded and the Minoan's culture reached neighbouring regions.

Palaces were contrived with multi-story structures upon intricate layouts, featuring courtyards, storerooms and workshops. As skilled seafarers engaging in maritime trade, contact was mantained with Egypt, the Levant, Anatolia and the Greek mainland. Art and pottery, and crops like barley, wheat, olives and grapes, made the bulk of goods that were traded. The Minoans also developed a writing script, which today remains largely undeciphered.

The height of their culture occurred between 1700 and 1450 BC. During that time period, there occurred the explosive eruption of the Thera volcano in the Aegean Sea, some 68 mi. north of Crete, in which the island was obliterated. But though the event likely had an effect on the Minoans, it's not the reason for their demise. Meaningful decline occurred in the half-century after 1450 BC, when internal conflicts produce violence and upheaval; the island would also be raided from the sea at the time. For about two centuries, the arrival of the Mycenaeans brought about a sharing of culture and trade. Yet in 1200 BC, the Minoan culture was inexplicably destroyed and abandoned, marking the end of their civilisation.

Mycenaeans

The Mycenaean peoples emerge between the 16th and 15th centuries BC, migrating south into the Greek mainland from the continent. Ruled by a warrior aristocracy, their agrarian society consisted of labouring free persons and slaves. As skilled warriors, the Mycenaeans engaged in trade and conflict with other cultures, notably the Minoans and Hittites.

They're best known for their construction of massive fortresses and palaces, employing the use of large, irregularly-shaped stone blocks without mortar. Advances were made in metalworking and craftsmanship, a more simplified writing system based on the Minoan model, agricultural innovations and advanced shipbuilding techniques. Developing advanced military technologies, using bronze swords, spear tips and armour, as well as chariots, they possessed a prowess that made them feared in battle. For the most part, these advancements were built upon the knowledge and influence of earlier Minoan advances.

While the civilisation was at it's height between the 14th and 13th centuries BC, within a century the Mycenae culture experienced a rapic collapse. Illiteracy led to a period of technological regression, which coincided with a period of internal strife. The depletion of resources and the destruction of multiple palaces suggests a civil war — while at the same time, Dorian peoples from the north, among other groups, caused a severe dissolution. The period would herald a great mythological tradition of Greek Olympus, the Trojan War and profound heroes such as Theseus, Hercules, Achilles and Odysseus. That the events surrounding these myths fell into the "dark age" that followed the Mycenaean collapse is intriguing.

Harappan Culture

Interactions between indiginous groups and migrants brought about a flourishing of culture in the region of the Indus River valley, sometime in the late 4th millennia BC. At cities such as Harappa and Mohenjodaro, the fertiled floodplains of the river encouraged a complex agricultural society in which settlements had well-organised street grids, advanced drainage systems and multi-story buildings made of fired brick. The people engaged in extensive trade within their civilisation and with both Mesopotamia and India. Written records did exist, as fragments have been found, but never a complete example. The civilisation thrived for 13 to 14 centuries.

Cities possessed public baths, granaries and citadels, all fashioned from standardised bricks. Standardisation was also applied to weights and measures. Pottery was known for its high quality and intricate designs. The Harappans were proficient in metallurgy also, fashioning objects made of gold, copper and bronze. Religious practices are speculative; most likely, the people continued to follow animism and were never contacted by the gods.

Beginning around 1900 BC, the region saw significant declines on the availability of water; signs point to a shift in the Indus River basin, which disrupted irrigation systems vital for food production. It's unknown if social unrest or conflicts contributed to the culture's demise; alternatively, some form of epidemnic may have devastated the population, resulting in a scattering of peoples and a widescale loss of knowledge. The period of complete decline likely took hundreds of years.

Indian Culture

- Main Article: Indian History

Various cultures across different regions of the Indian subcontinent were relatively dispersed. The use of bronze did occur upon the Gangetic plains and parts of eastern India. In Western India, the Ahar-Banas culture, situated in later Rajasthan, developed copper and bronze tools and ornaments, along with pottery, between 2500 and 2000 BC. Other cultures associated with bronze-making include the Malwa of central India and the Pandu. The latter are associated with megalithic structures such as dolmens, standing stones and cairns, the latter arranged in stone circles.

Vedic Culture

Prior to 1500 BC, the appearance of two distinct groups began a process of cultural exchange, assimalation and coexistence. The first, the Kolarians, had been spreading from the east for centuries prior to the "Vedic Period," bringing subsistence agriculture, traditional music, dance and religious rituals. The Dravidians were indigenous to the southern parts of India, and apparently separate from other cultures of the region like the Pandu.

Within the cultural mix of these peoples, the intervention of gods brought about the composition of the Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism. The Rigveda consists of hymns dedicated to various deities and natural forces — notably Indra and Agni. A social caste structure arose in tribal communities, restricting the individual's relationship to religious beliefs, daily life and social norms, while villages became organised around pastoralism and agriculture.

Chinese Culture

- Main Article: Chinese History

The Yangshao culture of the Chalcolithic began to establish more permanent settlements as the Bronze Age opened, which contributed to the rise of Longshan Culture along the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River after 2500 BC. Known for its distinctive black pottery, the Longshan would feature larger, more complex settlements and a greater social complexity — though minimal use of bronze metal took place. Nonetheless, the culture laid the groundwork for the subsequent Erlitou Culture, centered in the central plains south of the Yellow Basin.

Practicing an advanced metallurgy, the Erlitou period (1900 to 1500 BC) saw a proliferation of bronze use, though for simple objects such as tools, ornaments and ritual vessels. The emergence of a complex city spawned technological innovations like pottery, agriculture and metallurgy continued to develop, influencing social structures and economic activities. Cities had planned layouts, rammed earthen walls and palace-like structures.

By 1600 BC, China was on the cusp of the Shang Dynasty, a crucial period in ancient Chinese History. Shang culture would displace the Erlitao over a century and a half, introducing a written script and more complex bronze casting, especially weaponry and chariot fittings. Cities underwent more deliberate urban renewals, with walled enclosures, royal tombs and administrative structures. Trade and diplomatic relations were carried on with settlements along the upper Yellow river, the Sichuan basin and with steppe nomads. This trade would contribute to the growth of the Zhao peoples in the west, who would supplant the Shang, who by the end of the Bronze Age had shown marked signs of decline.

Vepsian Empire

- Main Article: Gnomish History

During the Chalcolithic Period, scattered gnomish tribal lands of the Neolithic demonstrate a natural affinity for nature enable them to develop an intimate understanding of placer mining and metallurgy, mastering bronze crafting as the Bronze Age begins. For protection, villages are built as semi-underground complexes with easy access to the surface and agricultural fields; this arrangement provides resistance against the harsh climate north European forests and plains.

A series of pre-Vepsian cultures emerge as gnomish technological achievements accelerate: notably Harn in the east, near the Volga Bend, and Nanbrun in present-day Norway. Vepses itself gathers a coalition of villages surrounding Lake Ladoga and forests to the south. All three, and others, succeed in producing harder alloys of bronze — nearly as hard as iron — along with small scale mills that employ water and wind power. This skill in harnessing natural energies becomes a hallmark of their society.

Trade between these gnomish entities permits a sharing of knowledge and peaceful coexistence, which by 2400 BC succeeded in created an electoral gnomish "empire," the Vepsian, stretching from the realms of Vastenjaur, in present day Sweden, to Harn. Nanbrun was nominally detached, but shared in trade benefits, as did multiple halfling and human communities within and adjacent to the extant empire. Vepses became a melting pot of northern cultures and knowledge.

However, as aggressive species such as gnolls and orcs encroached on its eastern borders, many gnomish tribes resented the ideals of war and instead gave way to these outsiders. The region of Harn alone developed a militaristic attitude, even as neighbouring gnomes migrated away, depopulating many regions. By 1800 BC, elvish expansion brought about a series of treaties in which gnomes surrendered forests north and west of Ladoga. The lack of communication between regions led to a leadership crisis, weakening the emperor's grip on the entity as a whole; and as trade routes withered, a technological stagnation took place. By the end of the Bronze Age, the empire had ceased to exist in all but name, while other races occupied what were once gnomish lands.