Egyptian History

Egyptian History centers on the Nile Valley, which remained uninhabited by humans until after the last Ice Age. As the once-verdant Sahara plateau underwent desertification, both people and animals were forced to migrate—some toward the Mediterranean, others eastward to the Nile. During the Palaeolithic, human communities occupied the cliffs overlooking the valley. In the Neolithic, early agriculturalists moved down to the valley floor, where they cultivated crops in the fertile soil left by the Nile's seasonal floods. This annual inundation enriched the land with nutrient-rich silt, making sustained agriculture possible and shaping the rhythms of Egyptian life and culture.

Contents

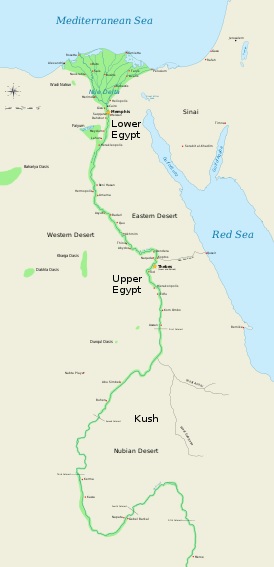

By this time, as many as forty agricultural communities had formed along the Nile north of the First Cataract, strung like beads along the river’s fertile edge. By around 5000 BC, these settlements had coalesced into two distinct kingdoms: one in the delta region, known as Lower Egypt, and the other in the Nile Valley, or Upper Egypt. This period marked the emergence of key cultural, social, and technological patterns that would come to define Ancient Egyptian civilisation. After centuries of conflict during the Chalcolithic period, the two kingdoms were unified under King Menes, also known as Narmer, who founded his capital at Memphis in the northern Nile Valley. This unification marked the beginning of Egypt’s 1st Dynasty.

Early Dynastic Period

Lasting from 3200 to 2800 BC, the Early Dynastic marks the emergence of the pharaonic civilisation. During this era, the rulers of Egypt established a centralised state, consolidating the authority of the pharaoh while building a bureaucratic framework to oversee the administration of the realm and its regional officials. Hieroglyphic writing developed rapidly, and the pharaohs began constructing elaborate royal tombs as expressions of their divine status. Agriculture remained the foundation of the economy, supporting the growth of trade and craftsmanship.

Religion was central to society. The pharaoh was regarded as a divine intermediary, receiving messages directly from the Gods—a belief mirrored in contemporary Mesopotamia. Temples multiplied, and religious practice evolved in response to a polytheistic awakening. Yet, this divine order clashed with the emerging ambitions of mortals, resulting in unrest that ultimately laid the groundwork for the Old Kingdom.

Artistic conventions began to take form, laying the foundation for Egypt’s distinctive visual language in sculpture, relief, and statuary. These conventions reflected the hierarchical structure of society, with proportions and poses reinforcing status and divine authority. Monumental architecture was still in its infancy, but early mastabas — bench-shaped tombs — hinted at the funerary sophistication that would define later dynasties. Trade routes expanded both within and beyond the Nile Valley, reaching into the Sinai for copper and into Nubia for gold, while contact with the Levant introduced new materials and ideas. The role of the palace became increasingly ceremonial as the bureaucratic class took on administrative burdens, marking the beginning of a complex relationship between the image of the pharaoh and the machinery of the state.

Old Kingdom

This lasted from 2780 to 2270 BC, spanning the 3rd to 6th Dynasties. The capital remained at Memphis. This era includes the most renowned pyramid builders of the 4th Dynasty. Zoser (Djoser) of the 3rd Dynasty commissioned the step pyramid at Saqqara, while Cheops (Khufu), Chephren (Kha-ef-Re), and Mycerinos (Men-kau-Re) of the 4th Dynasty built the great pyramids that still stand at Gizeh. These structures were not only symbolic expressions of royal authority—they also demonstrate the immense wealth and power wielded by 4th Dynasty rulers. The vast resources poured into constructing these royal burial chambers ultimately contributed to the gradual weakening of the state, a decline that became increasingly evident through the 5th and 6th Dynasties.

Advanced construction techniques reached new levels of refinement, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of geometry, material handling, and architectural balance. Quarrying systems enabled the mass extraction of limestone from Tura and granite from Aswan, used not only for temples and monuments but for the smooth, white casing stones that still covered the pyramids at Gizeh, which gleamed in the sun as brilliant, flawless monuments to royal authority. These were surrounded by expansive funerary complexes, causeways, mortuary temples, storage chambers, and administrative buildings, forming the core of a living religious and political landscape. Irrigation systems using canals and dikes were engineered to manage the seasonal flow of the Nile, stabilising agriculture and population growth. Artisans refined bas-relief into a narrative form, developed precise techniques of proportion and scale, and produced detailed statuary that reinforced social and divine hierarchies. Surveying methods allowed accurate land demarcation even after the disruption of annual floods, supporting taxation, inheritance, and central oversight.

The Old Kingdom collapsed after 2300 BC, as internal coherence unraveled under the weight of decentralised wealth and power. With regional governors acting autonomously and central leadership diminished, Egypt entered a prolonged period of instability and fractured rule. The 7th and 8th Dynasties emerged during this time, but held little effective power, and the country descended into disunity and feudal rivalry that endured for nearly four centuries.

Middle Kingdom

The Middle Kingdom lasted from 2143 to 1790 BC, encompassing the 9th to 12th Dynasties. Ruling from Thebes, the early dynasties of this period labored toward the restoration of central authority after centuries of fragmentation. Progress was gradual at first, but by the 12th Dynasty, under the leadership of Amenemhet I and his son Sesotris I, Egypt was once again unified and internally stable. These kings curtailed the independence of regional nobles, replacing them with appointed governors loyal to the crown, thereby reasserting pharaonic control over the provinces. Major building projects were commissioned, including new temples and pyramids at El-Lisht and early work at Karnak, marking a revival of state-sponsored architecture and the reestablishment of centralized religious power.

Egyptian influence expanded southward through military and commercial expeditions into Nubia, where fortresses were constructed above the First Cataract to secure trade routes and mineral wealth. These campaigns also served to project Egyptian authority beyond its traditional borders. Shipbuilding techniques improved significantly, with the development of more durable and navigable river craft, enabling more efficient transport along the Nile and into foreign waters. This facilitated an increase in trade not only with Nubia, but with regions across the Red Sea and into the Levant. Egyptian merchants, for the first time, began appearing in substantial numbers beyond their native lands, and exotic goods such as incense, ivory, timber, and lapis lazuli became more common in Egyptian markets.

In art and architecture, the Middle Kingdom produced significant advancements. Statues and reliefs achieved greater realism in the depiction of human features, moving away from the formal rigidity of earlier periods. Temples became more complex, incorporating elements like colonnades, massive pylon gateways, and stylized papyrus columns. The casting of bronze and the alloying of metals saw technical improvements, supporting both functional tools and ornamental objects. Pottery became more refined, and textile production grew in quality and quantity, suggesting a thriving artisan class supported by a revitalized economy.

Sesotris III (1887–1849 BC) was among the most powerful rulers of the period, leading campaigns deep into Syria and establishing military outposts along the eastern frontier in what became known as the Ways of Horus. These fortified checkpoints served not only military purposes but also as customs stations for trade and points of administrative control. His reign marks the height of Middle Kingdom power and territorial ambition.

Yet the Middle Kingdom's stability began to erode in the decades following Sesotris III. Corruption crept back into the bureaucracy, and agricultural output declined, weakening the state’s financial base. Internal disputes over succession fractured the royal line, undermining the central government's ability to respond to emerging threats. During this time, foreign populations, notably the Hyksos, began to infiltrate the eastern Delta. Over time, their influence grew, until they succeeded in dominating much of Lower Egypt. This ushered in the Second Intermediate Period, a span of roughly 150 years marked by disunity, foreign rule in the north, and a diminished role for Egypt on the international stage.

New Kingdom

Lasting a much briefer time, from 1555-1090 BC, comprising the 17th to 20th dynasties. By 1600, the development of a strong Egyptian movement succeeded in the expulsion of the invaders. Sekhem-Re, a good soldier who became the first pharoah of the 17th Dynasty, uprooted the last of the old oligarchy and confiscated their lands. With unity and order re-established in Egypt, the government was centralised and administered by an extensive bureaucracy. Under the pharoahs of the 18th Dynasty (to 1350 BC), Egypt acquired an empire in Syria and became the most powerful state in the Near East.

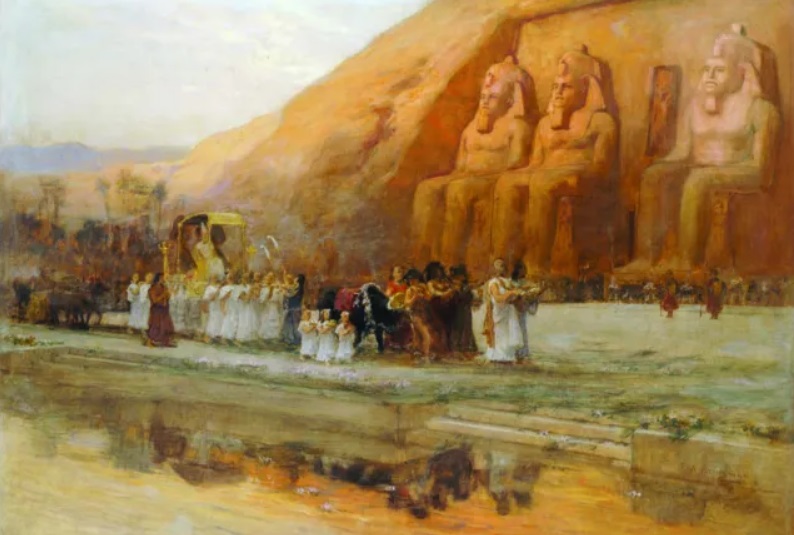

Significant advances were made in the arts of war, including the use of composite bows and horse-drawn chariots. The massive columns of Karnak were raised, completing the temple, as well as monuments at Luxor and elsewhere, that would leave a legacy that continues to amaze and inspire into the present day. The new Egyptians excelled at glassmaking techniques, including the use of blown vessels. Great strides were made in medical knowledge, mathematics, magic, shipbuilding and navigation.

Conquests

Amenhotep I, 1555-1540 BC, was the first of Egyptian rulers to reach the Euphrates — but it was a later ruler, Hatshepsut, sister and wife of Thutmosis II, who then also married Thutmosis III who conquered Syria in the course of almost two decades of annual campaigning. It was Thutmosis III who was the victor at Megiddo and Kadesh, who became scourge of the Mitanni (the word "armageddon" comes from Megiddo). The favour of Thumosis III was sought even by the then remote Hittites of Asia Minor. His gains were consolidated by his successors, Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV (d.1411).

Thutmose IV allied himself with the Mitanni against the Hittites, even marrying the daughter of the Mitanni king. His successor, Amenhotep III (Memnon) (1411-1375 BC) advanced Egypt's political influence to the highest point. Amenhotep's reign is seen as a golden era in Egyptian history, characterised my monumental architecture, artistic achievements and diplomatic successes. All nations feared Egypt and courted her favour.

Decline

After Amenhotep III's death and the accession of his son, Amenhotep IV, decline was rapid. Amenhotep IV changed his name to Ikhnaton, choosing to ignore the needs of empire and devote himself to religious reforms. This led to a defeat by the Hittites against the unsupported Mitanni kingdom, scattering the Syrian princes, threatening Egypt's northern border. Amenhotep's death left a boy-king, Tutankhamen, who fared no better as Egypt came to be pressed on every border.

The process of disintigration was temporarily stayed by the general, Horemheb, the last ruler of the 18th Dynasty. He was succeeded by a pharoah named Ramses I, who founded the 19th Dynasty — though he lived only a year. His son, Seti I (1290-1279 BC), temporarily halted the advance of the Hittites, while working to stabilise and strengthen Egypt's position. This allowed Ramses II (1292-1225 BC) to raise an army sufficient to defeat the Hittites at Kadesh (1274 BC). He could not push the Hittites from Syria, however; therefore he signed a treaty with them in 1266 BC, recognising their claims to the north. The southern part of Syria remained a part of Egypt.

Yet the end of the 13th century BC found Egypt threatened by new perils. Sea raiders (Philistines and others) plundered the Delta as Libyans pressed in from the west. While the Hittites had become allies, they were now harried by other tribes in the north. Rameses III (1198-1167 BC), the second pharoah of the 20th Dynasty, repelled the worst of the invasions, but the empire was lost. The drain on Egyptian finance and manpower, occasioned by continuous wars, at last brought about complete collapse at the end of the 12th century BC.

See also,

Bronze Age

Ptolemaic Egypt

World History