Abbassides (dynasty)

The Abbassides, also known as the Abbasids, were the second great dynasty of the Moslem Empire, tracing their lineage to Abbas, the uncle of Mohammed. Their rule began in 750 AD after a successful revolt against the ruling Ommiad (Umayyad) caliphs, a movement largely fueled by Persian discontent with Arab dominance. This shift in power marked a turning point, as the Abbassid caliphs leaned more heavily on Persian administrators and culture, bringing about a golden age of learning, science and governance.

Contents

Under the leadership of Al-Mansur (754–775), the Abbassids moved the capital from Damascus to Baghdad, a newly constructed city on the Tigris River. This city grew into the heart of an empire that embraced a cosmopolitan society, allowing non-Arabs to rise to power and fostering the revival of Persian, Hellenistic and Indian influences. With Baghdad as its center, the empire flourished, producing advancements in astronomy, medicine, mathematics and philosophy, guided by scholars such as Al-Khwarizmi, who developed algebra, and Hunayn ibn Ishaq, who translated Greek medical texts.

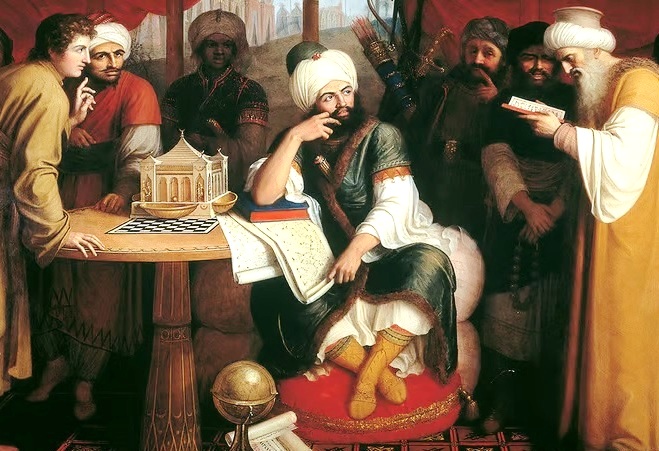

The dynasty reached its height under Harun al-Rashid (786–809) and Al-Mamun (813–833). Harun's reign is immortalised in the Arabian Nights, reflecting the opulence of his court, while Al-Mamun founded the House of Wisdom, a major center of translation and scholarship that drew on texts from across the known world. However, this period of luxury and learning diverged sharply from the strict austerity of early Islam, a shift that led to internal conflicts and resentment.

Decline

By the mid-9th century, the empire faced decline. The Caliph Motassem (833–842) introduced Turkish slave-soldiers (Mamluks) as his personal guard, a decision that would ultimately weaken Abbassid authority. Over time, these Turkish forces seized power for themselves, reducing the caliphs to puppets by the 10th century. Provinces such as Egypt, Persia and Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) declared independence, further fragmenting the once-unified empire.

Despite this decline, the Abbassid caliphs retained symbolic religious authority, even after the catastrophic Mongol sack of Baghdad in 1258, which saw Hulagu Khan slaughtering tens of thousands and effectively ending the dynasty's political power. The surviving Abbassids fled to Egypt, where they continued as nominal religious leaders under the Mamelukes, though they wielded no real influence.

This vestige of Abbassid authority lasted until 1517, when the Ottoman Sultan Selim I conquered Egypt and forcibly took the title of caliph. The last Abbassid caliph, Al-Mutawakkil III, was brought to Constantinople as a prisoner, where he was compelled to surrender any remaining claim to the caliphate. From that moment, the Ottoman sultans claimed the mantle of spiritual leadership over the Islamic world, marking the final end of the Abbassid line.

In 1650, the Abbassids are remembered as a bygone dynasty, their legacy preserved in the intellectual and cultural achievements that shaped the Islamic world. Baghdad, once the jewel of civilisation, has never fully recovered from its Mongol destruction, now serving as an Ottoman provincial capital, far removed from its former splendor. The caliphate, once a position of immense power, remains in the hands of the Ottoman sultans, though its significance is increasingly ceremonial.

See Dark Ages