Savanna (range)

Savanna describes a transitional biome between dense forest and arid plain, defined by a landscape of open grassland interspersed with trees that stand far enough apart to prevent their canopies from overlapping. These trees may be sparse and isolated or distributed with even regularity, depending on local soil and moisture conditions. The presence of large grazing and browsing herbivores — along with periodic wildfires, both natural and deliberate — prevents the establishment of dense undergrowth, limiting the spread of shrubs and saplings. In their place, tall grasses dominate, often growing to heights of six feet or more. Particularly robust species, such as elephant grass, can reach up to ten feet in height, forming dense thickets during the height of the wet season.

Savannas are most commonly found in the interiors of continents, situated between 5° and 15° latitude from the equator on both hemispheres, beyond the margins of equatorial rainforest but well within the influence of tropical weather systems. These lands are profoundly shaped by a climate that swings between extreme wet and dry seasons. From May through October, torrential rains fall with an intensity comparable to that of rainforests, swelling rivers, flooding lowlands and allowing rapid vegetative growth. This period is vital for planting, herding and storage. But from November to April, the rains vanish and the land transforms — heat builds, the soil cracks and desert-like conditions emerge. Grasses wither and trees shed leaves or withdraw sap to survive.

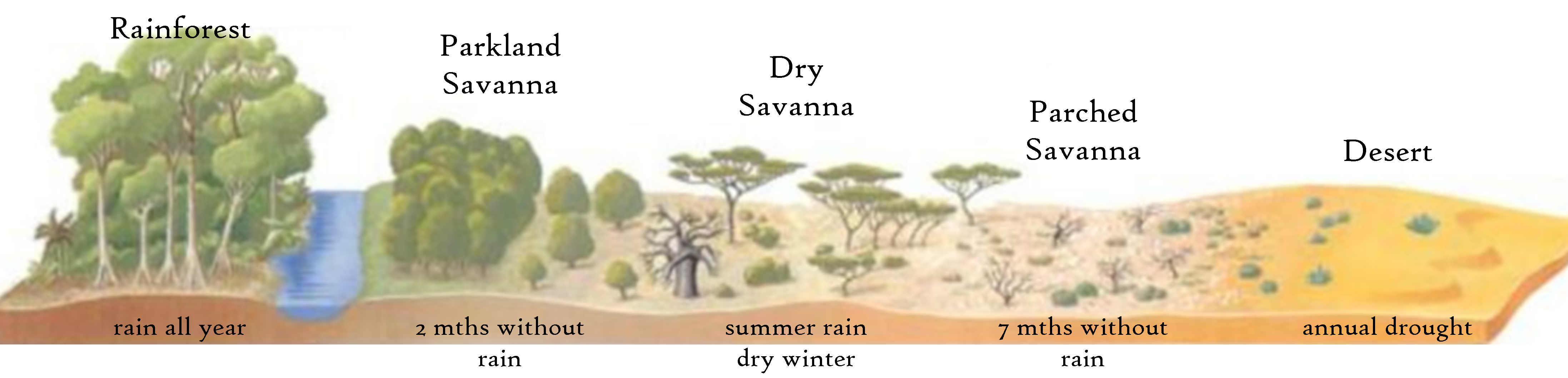

Savanna types are commonly distinguished by the impact of rainfall and soil depth. In parkland savanna, consistent moisture allows for clusters of trees, forming lightly forested meadows. In dry savanna, tree cover is scattered and irregular, often clinging to slight depressions or streambeds. Parched savanna appears more scrubland than grassland — marked by sandy soils, thorny bushes and stretches of barren ground where only the hardiest vegetation endures.

Because the soil structure allows most moisture to be absorbed near the surface, rather than sinking into deep aquifers, water scarcity becomes a critical concern during the dry season. Shallow wells and ephemeral water holes often dry out by mid-season, leaving communities and herds dependent on major rivers, underground cisterns or stored water caches. This cyclical hardship shapes settlement patterns and movement across the savanna, favouring seasonal migrations, drought-resistant crops and a cultural emphasis on water stewardship.

Conditions

At night, the rapid cooling of air across the savanna causes moisture to condense on the tall grasses, leaving the ground slick and damp by early evening. Bedding directly upon this surface invites discomfort and illness, and those familiar with the region know to lay down dry leaves or thick mats to insulate against the wet. More cautious travellers or residents rely on canvas shelters or lightweight tents, which not only offer dryness but critical protection from the many insects that thrive in the humid dark. Where trees are available, hammocks are strung between trunks, keeping bodies and supplies off the ground, away from both moisture and vermin.

Firewood must be taken directly from the trees, as downed branches are scarce and often infested or rotted. The trees of the savanna bear tough, fibrous wood, which splinters under axes and is better handled with curved machetes. These tools, preferred by locals, are essential for clearing space, shaping supports or preparing cooking fuel. Goods and cargos are never left resting on the earth. Instead, they are raised upon lattices of branches or set within slung carriers to promote air circulation and prevent spoilage. Even during dry periods, the daily cycle of heat and humidity threatens to rot fabric, grain and leather if care isn't taken.

Insects are an unceasing nuisance. Clouds of stinging flies, mosquitoes and gnats swarm around still air and open wounds. Those who can afford it travel with gauze curtains or netting, hung carefully over bedding and workspaces. These barriers do more than provide comfort; they serve as the primary defence against deadly insect-borne diseases such as malaria and sleeping sickness, both of which are endemic in parts of the savanna and shape local patterns of movement, settlement and survival.

Savanna Belts

Savanna culture is shaped above all by the availability of groundwater, which determines the density of vegetation, the stability of settlement and the patterns of life. Along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert, vast bands of distinct savanna types form a gradual transition from desert to woodland, each marked by differing rainfall, soil moisture and vegetation cover. These bands run from south to north across Africa, supporting a wide range of environmental adaptations:

The open expanse of the savanna gives rise to a hybrid culture — part pastoralist, part agriculturalist — where mobility and seasonal rhythms define existence. The sweeping plains favour herding and long-distance travel, encouraging nomadic or semi-nomadic lifeways, while the more stable zones near rivers or beneath shallow aquifers foster farming communities with permanent dwellings and irrigated fields. Where groundwater is abundant, cities emerge: shaded by groves of trees and surrounded by patterned cultivation, fed by wells or flowing canals. These urban centres may serve as trade hubs, spiritual centres or seats of local kingship. In contrast, regions with limited water demand a harder, more transient life. Here, flocks are driven across miles of open land in search of grazing that vanishes quickly under the weight of hooves and the glare of the sun.

To maintain their way of life, herders frequently use fire as a tool. Large tracts of dry grass are burned deliberately — not only to reduce pests and clear old growth, but to renew the grasses that sprout quickly in fire-enriched soil. In doing so, they suppress the encroachment of woodland and expand the reach of the grassland itself. The practice deepens the divide between those tied to permanent agriculture and those who wander, and it often leads to disputes over land, water and access to critical grazing corridors.

Major Savannas

A list of the most extensive savannas in the world:

- Arnhem & Cape York - undiscovered Australia

- Caatinga - dry savanna, interior northeastern Brazil

- Cerrado - central Brazilian plateau

- Chapparal - California and Baja Peninsula

- Gran Chaco - lowland natural region of the Rio de la Plata

- Horn of Africa - dry savanna in far east Africa

- Llanos Orinoco - sedimentary basin in Venezuela

- Mexican Altiplano - dry savanna, north and central Mexico

- Middle Salween Basin - central Burma

- Puna - highland plateau in Peru

- Riverina & Darling River Basin - undiscovered Australia

- Sahel - progressive savannas from Senegal to Sudan

- Serengeti - east Africa along the Great Rift Valley

- South Congo Basin - dense savanna between the Congo and Angola

- Southwest Australian Savanna

Common Features

A list of elements and features that may be found in savanna ranges:

Savanna Creatures

A list of monsters that may be found in savanna ranges:

- African Elephant

- Ankheg

- Asiatic Elephant

- Axe Beak

- Bat (giant)

- Black Ant (giant)

- Boa Constrictor (giant)

- Boar (wild)

- Bonesnapper

- Bulette

- Bull Ant (giant)

- Carnivorous Ape

- Cheetah

- Couatl

- Cougar

- Crocodile

- Dog (wild)

- Dragonne

- Eagle (giant)

- Emu

- Frog (huge)

- Golden Jackal

- Griffon

- Hill Giant

- Hippogriff

- Hippopotamus

- Hyena

- Hylochloerus

- Jackalwere

- Jaguar

- Lamassu

- Leopard

- Lion

- Lizardfolk

- Mandrill

- Megalania Lizard

- Moa

- Mordenkainen's Tortoise

- Naga

- Rhea

- Spotted Lion

- Violet Fungus

- Warthog

See List of Ranges