Bronze Age (for deletion, kept for Palestinian details)

Egypt

In ancient times Egypt consisted of two parts: the Nile Valley north of the First Cataract, a narrow deep trench only a few miles wide and 600 miles long; and the Nile Delta, an inverted triangle 150 miles across. The combined inhabited area of the valley and the delta was about 10,000 square miles.

As the ancient writer Diodorus pointed out, Egypt was "fortified by nature," with the cataracts in the south, the desert on the east and west, and the sea to the north — but it was also isolated by these natural barriers, with the result that there developed in Egypt a civilization that was quite different from the other cultures of the Near East. Moreover, dominating almost every phase of Egyptian culture was the Nile River, the most striking topographic feature of the country, which provided Egypt with its fertility and its principal means of communication.

The Nile Valley was not occupied by man until after the last Ice Age, when the Sahara Desert began to increase in size and drove the men and animals from northern Africa toward the Mediterranean coast or eastward to the banks of the Nile. The men of the Paleolithic Age lived on the high cliffs above the valley, but their successors, the agriculturalists of the Neolithic Age descended to the valley floor to plant their crops.

In prehistoric times, (8000-3200 B.C.), there were perhaps forty agricultural communities, or states, strung like beads along the ribbon of the Nile north of the First Cataract. By about 5000 B.C. Egypt had been unified to the extent that there were two kingdoms: one in the Delta (Lower Egypt) and one in the Valley (Upper Egypt). After many centuries of warfare the two kingdoms were combined, traditionally by King Menes of Upper Egypt, into a single realm about the beginning of the Dynastic Period (3200 B.C.).

For convenience in chronology, the rulers of Egypt are identified by dynasties, each dynasty being made up of a succession of rulers belonging to a single family or tracing descent to a common ancestor. Reigning dynasties came to an end as a result of the accession to the throne of rulers from another line or family. In the early Dynastic Period (3200-1900 B.C.), three main subperiods are of special interest and importance: the Old Kingdom (Dynasties III – VI, 2780-2270 B.C.); the Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI – XII, 2143-1790 B.C.); and the New Kingdom, or Empire (Dynasties XVIII – XX, 1555-1090 B.C.). In these subperiods, Egypt was most completely unified and prosperous, and the most outstanding cultural advances were made.

The Old Kingdom

The Pharoahs of the Old Kingdom were the famous pyramid builders: Zoser (Djoser) of the 3rd Dynasty, whose step pyramid was constructed at Saqqara, and Cheops (Khufu), Chephren (Kha-ef-Re) and Mycerinos (Men-kau-Re) of the 4th Dynasty, whose pyramids still stand at Gizeh. During this period the capital of Egypt was located at Memphis, in the northern part of the Nile Valley. While agriculture flourished in Egypt itself, trade relations were established with Phoenicia, the islands of the eastern Mediterranean, and Nubia to the south. Sinai, important as a source of copper, was brought under Egyptian control. The great pyramids are not only symbolic; they are also indicative of the power and wealth of the 4th Dynasty rulers. It has been conjectured that the huge funds lavished upon these royal burial chambers were responsible for the gradual weakness and decline of the Old Kingdom, which became more and more apparent in the time of the 5th and 6th Dynasties, and culminated in political and economic collapse after 2300 B.C. At any rate, the central power waned while local authorities gained strength, with the result that Egypt fell into a disorganized feudalism which lasted for almost four centuries.

The Middle Kingdom

This subperiod opened with the rise of a strong power at Thebes in the south. By the time of the 12th Dynasty (2000 B.C.), Egypt had progressed a long way on the road to reunification. Under Amenemhet (2000-1980 B.C.) and Sesotris I (Se’n-Wosret I) (1980-1950 B.C.), the feudal nobility were disciplined, and Egypt began to penetrate south of the First Cataract. Sesotris III (1887-1849 B.C.) even carried the Egyptian standards into Syria in the first military display of Egypt in that direction. The Middle Kingdom is the classic period of Egyptian art and literature, when the canons of Egyptian taste were established. Once more agriculture prospered, and trade with Syria and Nubia increased in volume. Egyptian merchants also began to appear along the Red Sea. The period ended in confusion and was followed by the invasion of the delta by the Hyksos from Syria, and the collapse of the central authority in the valley.

The New Kingdom

The interval between the invasion by the Hyksos and the rise of the New Kingdom is rather shorter than the period which divides the Old Kingdom from the Middle Kingdom. By 1600 B.C., the presence of the Hyksos in the Delta had led to the development of a strong Egyptian nationalist movement aimed at the explusion of the invaders. Led by Sekhem-Re, a good soldier who became the first Pharoah of the XVII Dynasty, the Egyptians drove out the Hyksos (1600 B.C.). The new ruler then uprooted the last of the feudal lords and confiscated their lands. With unity and order re-established in Egypt, the government was centralized and administered by an extensive bureaucracy.

Height of Power

Under the Pharoahs of the XVIII Dynasty (1555-1350 B.C.), Egypt acquired an empire in Syria and became the most powerful state in the Near East. Amenhotep I (1555-1540 B.C.) was the first of the Egyptian rulers to reach the Euphrates, but it was a later ruler, Hatshepsut, sister and wife of Thutmosis II, and later of Thutmosis III (1501-1448 B.C.) who conquered Syria in the course of almost two decades of annual campaigning. Thutmose was the victor at Megiddo (Armageddon) and Kadesh, and the scourge of the Mitannians; his favor was sought even by the then remote Hittites of Asia Minor. His gains were consolidated by his successors, Amenhotep II (1448-1420 B.C.) and Thutmose IV (1420-1411 B.C.). The latter allied himself with the Mitannians against the Hittites and married the daughter of the Mitannian king. Under Amenhotep III (Memnon) (1411-1375 B.C.), the political influence of Egypt reached its highest point. Amenhotep’s reign was noted for its peace and prosperity; all other nations feared Egypt and courted the favor of her rulers.

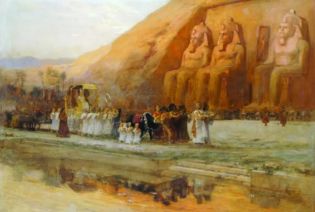

After Amenhotep’s death, however, and with the accession of his son, Amenhotep IV, decline was rapid. While Amenhotep IV, who for religious reasons changed his name to Ikhnaton, ignored the empire and devoted himself to religious reforms, the Hittites won over the Mitannians and the Syrian princes, and began to penetrate the northern boundaries of the Egyptian empire. The boy-king Tutankhamen fared no better. The process of disintigration was temporarily stayed by the general, Horemheb, and his successors of the XIX Dynasty, who ascended the throne in the latter part of the 14th century B.C. Seti I temporarily halted the advance of the Hittites, and his son, Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.), met them in a great battle at Kadesh in 1288 B.C. Unable to push the Hittites from Syria, Rameses signed a treaty with them in 1266 which recognized their claim to the northern area and retained southern Syria for Egypt.

The end of the 13th century B.C. found Egypt threatened by new perils. The sea raiders (Philistines and others from the north) were plundering the Delta as the Libyans pressed in from the west. The Hittites, who might now have become valuable Egyptian allies, were even more harried than the Egyptians by peoples from the north. The great Pharaoh of the XX Dynasty, Rameses III (1198-1167 B.C.), repelled the worst of the invasions, but the empire was lost, and the drain on Egyptian finance and manpower occasioned by continuous wars at last brought complete collapse at the end of the 12th century B.C. For the next four hundred years, Egypt was weak and disorganized under a succession of Egyptian, Libyan and even Nubian kings.

Continued in The Dark Bronze Age

See Also,

History

The Chalcolithic Period