Difference between revisions of "Bronze Age (for deletion, kept for Palestinian details)"

Tao alexis (talk | contribs) (→India) |

Tao alexis (talk | contribs) (→India) |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

Another notable development was in the sphere of popular religion, where a synthesis was effected between some Vedic deities and those that appeared to resemble them in the popular pantheon of the pre-Aryans. This process led to the emergence of Shiva and Vishnu, with Brahma as a distant third deity. The three gods, Trimurti, began to fill a large place in the affections of the people, and the many legends of their lives and deeds that fill the epics and the puranas undoubtedly embody much pre-Aryan lore. These legends became localized in different parts of India, and famous temples and shrines were erected everywhere. Pilgrimages to such centers and the rehearsal of the sacred legends connected with them have served through the ages as one of the most powerful bonds for uniting India. Temple worship and the doctrines of karma and transmigration came into vogue. The Ramayana of Valmiki, treating of the most popular story of Rama and his wife Sita; the kernel of the other great epic, Mahabharata, the story of the great war between the Kurus and the Pandus; and the core of the puranas (legendary history) must have been composed in this period also. Their continuous influence on the life and art of India can hardly be exaggerated. | Another notable development was in the sphere of popular religion, where a synthesis was effected between some Vedic deities and those that appeared to resemble them in the popular pantheon of the pre-Aryans. This process led to the emergence of Shiva and Vishnu, with Brahma as a distant third deity. The three gods, Trimurti, began to fill a large place in the affections of the people, and the many legends of their lives and deeds that fill the epics and the puranas undoubtedly embody much pre-Aryan lore. These legends became localized in different parts of India, and famous temples and shrines were erected everywhere. Pilgrimages to such centers and the rehearsal of the sacred legends connected with them have served through the ages as one of the most powerful bonds for uniting India. Temple worship and the doctrines of karma and transmigration came into vogue. The Ramayana of Valmiki, treating of the most popular story of Rama and his wife Sita; the kernel of the other great epic, Mahabharata, the story of the great war between the Kurus and the Pandus; and the core of the puranas (legendary history) must have been composed in this period also. Their continuous influence on the life and art of India can hardly be exaggerated. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 02:54, 24 November 2020

Contents

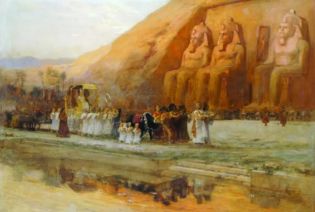

Egypt

In ancient times Egypt consisted of two parts: the Nile Valley north of the First Cataract, a narrow deep trench only a few miles wide and 600 miles long; and the Nile Delta, an inverted triangle 150 miles across. The combined inhabited area of the valley and the delta was about 10,000 square miles.

As the ancient writer Diodorus pointed out, Egypt was "fortified by nature," with the cataracts in the south, the desert on the east and west, and the sea to the north — but it was also isolated by these natural barriers, with the result that there developed in Egypt a civilisation that was quite different from the other cultures of the Near East. Moreover, dominating almost every phase of Egyptian culture was the Nile River, the most striking topographic feature of the country, which provided Egypt with its fertility and its principal means of communication.

The Nile Valley was not occupied by man until after the last Ice Age, when the Sahara Desert began to increase in size and drove the men and animals from northern Africa toward the Mediterranean coast or eastward to the banks of the Nile. The men of the Paleolithic Age lived on the high cliffs above the valley, but their successors, the agriculturalists of the Neolithic Age descended to the valley floor to plant their crops.

In prehistoric times, (8000-3200 B.C.), there were perhaps forty agricultural communities, or states, strung like beads along the ribbon of the Nile north of the First Cataract. By about 5000 B.C. Egypt had been unified to the extent that there were two kingdoms: one in the Delta (Lower Egypt) and one in the Valley (Upper Egypt). After many centuries of warfare the two kingdoms were combined, traditionally by King Menes of Upper Egypt, into a single realm about the beginning of the Dynastic Period (3200 B.C.).

For convenience in chronology, the rulers of Egypt are identified by dynasties, each dynasty being made up of a succession of rulers belonging to a single family or tracing descent to a common ancestor. Reigning dynasties came to an end as a result of the accession to the throne of rulers from another line or family. In the early Dynastic Period (3200-1900 B.C.), three main subperiods are of special interest and importance: the Old Kingdom (Dynasties III – VI, 2780-2270 B.C.); the Middle Kingdom (Dynasties XI – XII, 2143-1790 B.C.); and the New Kingdom, or Empire (Dynasties XVIII – XX, 1555-1090 B.C.). In these subperiods, Egypt was most completely unified and prosperous, and the most outstanding cultural advances were made.

The Old Kingdom

The Pharoahs of the Old Kingdom were the famous pyramid builders: Zoser (Djoser) of the 3rd Dynasty, whose step pyramid was constructed at Saqqara, and Cheops (Khufu), Chephren (Kha-ef-Re) and Mycerinos (Men-kau-Re) of the 4th Dynasty, whose pyramids still stand at Gizeh. During this period the capital of Egypt was located at Memphis, in the northern part of the Nile Valley. While agriculture flourished in Egypt itself, trade relations were established with Phoenicia, the islands of the eastern Mediterranean, and Nubia to the south. Sinai, important as a source of copper, was brought under Egyptian control. The great pyramids are not only symbolic; they are also indicative of the power and wealth of the 4th Dynasty rulers. It has been conjectured that the huge funds lavished upon these royal burial chambers were responsible for the gradual weakness and decline of the Old Kingdom, which became more and more apparent in the time of the 5th and 6th Dynasties, and culminated in political and economic collapse after 2300 B.C. At any rate, the central power waned while local authorities gained strength, with the result that Egypt fell into a disorganized feudalism which lasted for almost four centuries.

The Middle Kingdom

This subperiod opened with the rise of a strong power at Thebes in the south. By the time of the 12th Dynasty (2000 B.C.), Egypt had progressed a long way on the road to reunification. Under Amenemhet (2000-1980 B.C.) and Sesotris I (Se’n-Wosret I) (1980-1950 B.C.), the feudal nobility were disciplined, and Egypt began to penetrate south of the First Cataract. Sesotris III (1887-1849 B.C.) even carried the Egyptian standards into Syria in the first military display of Egypt in that direction. The Middle Kingdom is the classic period of Egyptian art and literature, when the canons of Egyptian taste were established. Once more agriculture prospered, and trade with Syria and Nubia increased in volume. Egyptian merchants also began to appear along the Red Sea. The period ended in confusion and was followed by the invasion of the delta by the Hyksos from Syria, and the collapse of the central authority in the valley.

The New Kingdom

The interval between the invasion by the Hyksos and the rise of the New Kingdom is rather shorter than the period which divides the Old Kingdom from the Middle Kingdom. By 1600 B.C., the presence of the Hyksos in the Delta had led to the development of a strong Egyptian nationalist movement aimed at the explusion of the invaders. Led by Sekhem-Re, a good soldier who became the first Pharoah of the XVII Dynasty, the Egyptians drove out the Hyksos (1600 B.C.). The new ruler then uprooted the last of the feudal lords and confiscated their lands. With unity and order re-established in Egypt, the government was centralized and administered by an extensive bureaucracy.

Height of Power & Collapse

Under the Pharoahs of the XVIII Dynasty (1555-1350 B.C.), Egypt acquired an empire in Syria and became the most powerful state in the Near East. Amenhotep I (1555-1540 B.C.) was the first of the Egyptian rulers to reach the Euphrates, but it was a later ruler, Hatshepsut, sister and wife of Thutmosis II, and later of Thutmosis III (1501-1448 B.C.) who conquered Syria in the course of almost two decades of annual campaigning. Thutmose was the victor at Megiddo (Armageddon) and Kadesh, and the scourge of the Mitannians; his favor was sought even by the then remote Hittites of Asia Minor. His gains were consolidated by his successors, Amenhotep II (1448-1420 B.C.) and Thutmose IV (1420-1411 B.C.). The latter allied himself with the Mitannians against the Hittites and married the daughter of the Mitannian king. Under Amenhotep III (Memnon) (1411-1375 B.C.), the political influence of Egypt reached its highest point. Amenhotep’s reign was noted for its peace and prosperity; all other nations feared Egypt and courted the favor of her rulers.

After Amenhotep’s death, however, and with the accession of his son, Amenhotep IV, decline was rapid. While Amenhotep IV, who for religious reasons changed his name to Ikhnaton, ignored the empire and devoted himself to religious reforms, the Hittites won over the Mitannians and the Syrian princes, and began to penetrate the northern boundaries of the Egyptian empire. The boy-king Tutankhamen fared no better. The process of disintigration was temporarily stayed by the general, Horemheb, and his successors of the XIX Dynasty, who ascended the throne in the latter part of the 14th century B.C. Seti I temporarily halted the advance of the Hittites, and his son, Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.), met them in a great battle at Kadesh in 1288 B.C. Unable to push the Hittites from Syria, Rameses signed a treaty with them in 1266 which recognized their claim to the northern area and retained southern Syria for Egypt.

The end of the 13th century B.C. found Egypt threatened by new perils. The sea raiders (Philistines and others from the north) were plundering the Delta as the Libyans pressed in from the west. The Hittites, who might now have become valuable Egyptian allies, were even more harried than the Egyptians by peoples from the north. The great Pharaoh of the XX Dynasty, Rameses III (1198-1167 B.C.), repelled the worst of the invasions, but the empire was lost, and the drain on Egyptian finance and manpower occasioned by continuous wars at last brought complete collapse at the end of the 12th century B.C. For the next four hundred years, Egypt was weak and disorganized under a succession of Egyptian, Libyan and even Nubian kings.

Mesopotamia

The Land between the Rivers is the name often applied to the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. Broadly speaking, Mesopotamia is the habitable area bounded by the Persian Gulf on the southeast, by the mountains of Iran and Asia Minor on the east and north, and by the deserts of the Levant and Arabia on the west and south. The major axis runs from northwest to southeast, and the two main topographical divisions are the highlands of the nouth and the plain of the south. In ancient times, it included the territory of later Babylonia and Assyria.

Human habitation of the highland area of Mesopotamia began at least as early as the Neolithic Age, but did not invade the plain, which was then swampy, until 5000 or possibly 4000 B.C. It was on the plain, however, that the first great civilisations arose. Later peoples, following the first penetration into the valley, swept onto the plain from the deserts and highlands to destroy and absorb, or create new periods of cultural endeavor. Thus the history of Mesopotamia may be subdivided according to the empires, dynasties and periods of eclipse that successively flourished and waned there.

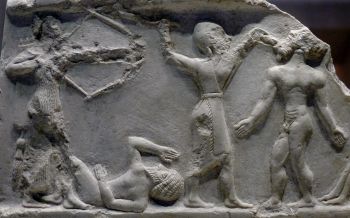

Sumeria & Akkad

The first civilised inhabitants descended from the mountains of Elam to the swampy plain at the head of the Persian Gulf, which became ancient Sumer. They drained the swamps, instituted flood control and established agriculture on a permanent basis. With the development of trade with the surrounding areas — Persia, Elam, Assyria, India and the Mediterranean coast — the Sumerian settlements grew into prosperous city states, which by 3500 B.C. possessed a mature civilisation characterised by urban life, metal working, textile manufacture, monumental architecture and an efficient system of cuneiform writing. Cultural traits included sculpture, astronomy for calendrical purposes and slavery.

the southern plain at the head of the Persian Gulf was dotted with Sumerian city states, which were theocratic. Each state was considered the property of a particular local god, who was represented on earth by a high priest (patesi) who was the religious and governmental head of his community and its surrounding territory. Geographic areas of great importance in this early period were the cities of Ur, Erech, Umma, Eridu, Lagash, Nippur, Sippar and Akkad, a Semitic state in the north. These states traded with one another. Interstate wars were common, and sometimes brief local empires were established when one state would conquer a few of its neighbours. About the middle of the 3rd millennium B.C., however, Semitic tribes from the Arabian Peninsula, who had settled in the northern Fertile Crescent and adopted Sumerian culture, became strong enough to endanger Sumerian independence.

Sargon of Akkad, 2637-2582 B.C., conquered the Sumerians and carved out an empire which stretched from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea. After perhaps 2500 B.C., however, the Akkadian power declined, and a new period of independence and prosperity began for the Sumerians; this is the era of the 3rd Dynasty of Ur and the greatness of Lagash under Gudea. Other important states included Isin and Larsa. At times the influence of the plain extended into the Assyrian highlands, which benefitted from the northward diffusion of Sumerian civilisation. The end came about 2000 B.C. with the rise of the Amorite kingdom, a new Semitic state. The Sumerians lost their independence forever, and the old areas of Sumer and Akkad were swallowed up by the empire of Old Babylonia.

Sumerian epics on the Creation and the Flood reflect considerable literary ability and appreciation.

Old Babylonia

The Amorite invasion came principally from the west. The Amorites established themselves at Babylon, uniting the plain once more, resulting in the establishment of what came to be known as the Old Babylonian Kingdom (distinct from later Babylon states). Hammurabi, the sixth Amorite king (1792-1750 B.C.), completed the process of Babylonian expansion by the establishment of an empire which included Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and parts of Syria. The city of Babylon was the capital of this wide realm.

Although the civilisation of the Babylonians was based upon that of the early Sumerians, due to Semitic influences the Sumerian elements in the population lost their identity. There were three main social classes: (1) an upper class composed of a feudal landed nobility, with the civil and military officials of the bureaucracy and the priests; (2) a middle class of merchants, craftsmen, scribes and professional men; and (3) a lower class of small landholders, urban and rural workers, and a horde of slaves. Under Hammurabi, the Babylonian government was a well-organized bureaucracy headed by the king and his ministers. The government concerned itself with national defense, administration of justic, the direction of agricultural production and the collection of taxes. The clay tablets which were the business documents of the Babylonians show an economic life amazing in its complexity; among the classs of business records represented are receipts, loans, contracts, leases, transfers, inventories and ledgers. Although private persons held large tracts of land, other land belonged to the crown or the priests. The land was worked by free persons, slaves and serfs. There were also tenant farmers, who might be either renters or sharecroppers.

Many Babylonian craftsmen owned their shops, but others worked in the palaces and temples for board and wages. The apprentice system was universal, and the craftsmen were enrolled in guilds with others who plied the same trades. There was trade with Egypt, Syria, the northern hills and India. In this trade the media of exchange were gold, silver and copper, and the Babylonian system of weights and measures became standard throughout the Near East. The Code of Hammurabi demonstrates the complicated institutional system and the rather advanced economic and business life of the country.

From this early Sumerian-Babylonian civilization have come many cultural traits in our own modern civilization. These ancient people were the first to employ the seven-day week and the 24-hour day (with twelve hours used twice). Great advances were made (for calendrical purposes) in the study of astronomy; astrology was also of great importance. The Babylonians mastered the various arithmetical processes and the simpler geometric manipulations concerned with land measurement. Babylonian algebra was more advanced than that of the Greeks.

During the reign of Samsu-iluna (1750-1712 B.C.), the empire began to fragment. During the endless battles against rebellions that occurred during his reign, the cities of Ur and Uruk were largely or completely abandoned, followed by Larsa, Nippur and Isin. Drought, war and pestilence spread by moving armies ravaged the countryside for the next century, until Babylon was sacked by the Hittites of Asia Minor in 1595 B.C., leading to a collapse of the empire.

The Kassites and Mitanni

Kassites from Elam descended upon the plain to destroy the last of the Amorite dynasty and replace it with kings drawn from their own ranks. Constituting a minority of nobles, holding their position by right of conquest, the Kassites were able to control the plain but could not maintain their authority in the highlands. These were controlled by warlike, predominantly Semitic peoples called the Assyrians, who began to lay the foundations for an empire larger than any of their predecessors. On the plain, however, the Kassites would rule until 1175 B.C.. Their culture relates them to the Aryan anvaders of India, but the cultural contribution of the Kassites was negligible. The major features of Babylonian civilisation remained unchanged.

Hurrians from the northern mountains would also rush in to exploit the power vacuum, overrunning the lands of Syria and the upper Euphrates, establishing the Mitanni Kingdom. By 1450 B.C., they had established their capital at Washukanni (location unknown), made the Assyrians into a vassal state and had driven the Hittites into the Anatolian highland. After successful clashes with the Egyptians, the Mitanni sought peace with them, forming an alliance against the Hittites.

By 1366 B.C., Mitanni influence over Assyria would wane. Dynastic wars of succession would weaken the kingdom, increasing both the Hittite and Assyrian threats. With the withdrawal of Egyptian diplomacy, the Hittites invaded Mitanni vassal territories in northern Syria. A Hittite army installed a puppet, Shattiwaza, on the throne in the late 14th century B.C. Washukanni was sacked again in 1290 B.C. by Assyrians, and in the 13th century, Shalmaneser I (1265-1235 B.C.) of Assyria annexed the remaining Mitanni territory.

Palestine

At the beginning of the 3rd millenium B.C. the kings of the early dynasties of Egypt were sending expeditions northward to conquer the Asiatic coastland in order to control its commerce and obtain timber, metals, and other raw materials. It was in this area that the goods of Egypt and Babylonia were exchanged. By the middle of the 2nd millenium B.C. the admixture of these two civilizations, with some Minoan additions, had produced a rich, complex society along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea. Fortified towns were built and the best harbors on the coast were utilized; inland, along caravan routes, walled cities such as Jerusalem appeared. Inhabiting the area were nomadic and semi-nomadic Semites such as Amorites, Canaanites, Aramaeans, and Hebrews whose mode of life is best portrayed in the Old Testament.

Toward the end of the 2nd millenium B.C. the Egyptian, Hittite, and Mesopotamian governments became disorganized and weak, thus enabling the smaller geographic regions between them to enjoy more liberty of action and some independence. It was in this era that Moses led the Hebrew people out of Egypt into Sinai and, finally, toward the Dead Sea and the Jordan River. At about the same time, however, the non-Semitic Philistines, coming from Crete or Asia Minor, invaded the Asiatic coastland, founded a powerful kingdom, and gave the country their name — Palestine.

Hittite Empire

The Hittites were a feudal state of Asia Minor established about the middle of the 3rd millenium B.C. The Hittites were invaders, probably not a large group, who conquered the natives and established themselves as the ruling caste. The Empire had at its head a hereditary ruler, the Great King. He was a war leader and a high priest, who was assisted by a council of the Hittite nobles. Outlying territories were ruled by vassals who were closely supervised by the Great King. The nobility was mainly confined to those of Hittite descent, while the native population formed a middle class of traders, artisans and soldiers. There was also a labour class. Despite the existence of trade and manufacture, the principle economic activities were agriculture and grazing. An important source of Hittite wealth and power was iron; the Hittites controlled the only extensive deposits of iron in the Near East.

Culturally, the Hittites were greatly indebted to the Babylonians. They borrowed from the Babylonians the cuneiform system of writing, and Hittite law codes clearly have Babylonian origin. The art of the Hittites, though basically Babylonian, shows considerable independence. Sculpture in stone and metal was common, and the Hittite artists produced both relief sculpture and figures in the round. Hittite palaces and fortifications were massive in character; they were constructed of stone and brick. Knowledge of Hittite religion is sketchy. In Asia Minor there was a sky god, and the worship of the Earth Mother, a fertility goddess, was very important. In the pantheon of the Hittites themselves, the sun and moon were deities of great significance.

By 1800 B.C. they controlled most of Asia Minor and were soon strong enough to raid Babylonia. With the decline of the Egyptian Empire in the 14th century B.C., they began to penetrate northern Syria, and a hundred years later the Egyptians under Ramses II were forced to acknowledge their claims to the area around Kadesh. Of the Hittite kings the names and deeds of those who reigned between 1400 and 1200 B.C. are best known. The first of these was Shubbiluliuma (1400-1360 B.C.) who made the initial advances into northern Syria. His successor was Murshil, who died about 1330 B.C. Next came Mutallu and Hattushil; the latter was a signatory to the famous non-aggression treaty with the Egyptians in 1266 B.C.

Persia

The Iranian plateau extends from the mountains east of the Tigris to the Indus Valley, and from the Persian Sea and Indian Ocean to the Caspian Sea and Jaxartes River. It is subdivided into the western parts of Elam and Persia, and the eastern parts of Sogdiana, Bactria, Aria, Drangiana and Arachosia. During the 3rd millenium, the Elamites occupied the lowlands adjoining the Persian Gulf, east of Sumer. The Kassites originated in the Zagros Mountains. The Aryans came to occupy the Iranian plain from the northeast around 1800 B.C., who would supplant earlier populations, with some of these tribes later becoming known as Persian.

Sumerians and Akkadians frequently defeated and subjected the Elamites, whose civilisation became fundamentally Sumerian. The Awan Dynasty (2350-2150 B.C.) collapsed when the Gutian people overran southern Mesopotamia from the east. The Elamites were reunited under the Shimashki Dynasty (2100-1970 B.C.). During this period, the Elamites, allied with Susiana, sacked the city of Ur, ending the 3rd Dynasty of that Empire (2004 B.C.). Ur was rebuilt and the Elamites expelled.

A 3rd Elamite dynasty, the Sukkalmah (1970-1770 B.C.), would grow rich with maritime trade along the shores of Africa and Asia, as well as the Indus Valley Civilisation. However, the influence of the Amorites of Babylonia would cause a steady decline, with the region falling into chaos and wars of succession until 1500. Thereafter, the region would be ruled over by Kassite kings with close ties to the Tigris-Euphrates plain.

India

Prehistoric Age

The earliest inhabitants of the country probably were the Munda or Kolarians, who once covered a very wide territory—place names scattered throughout northern India show traces of their presence. Later, a darker people, the Dravidians, appeared in India and soon spread over the entire country. The drove the original inhabitants before them into lands farther east, or pressed them back into the mountains and jungles of central and eastern India, where they still linger. The origin and affiliations of these newcomers are not clearly established, although recent studies point to Asia Minor and the highlands of Iran as their earlier habitations.

An ancient civilization, dating back to 2750-1800 B.C., dwelt in the valley of the Indus, particularly at Mohenjo-Daro, in Sind, and Harappa, in the Punjab. This resembled the civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. Remarkable brick buildings, statuettes in stone and metal, jewels, knives, and numbers of seals covered with undeciphered pictorial writing has been found. The metals used were gold, silver, copper, tin and lead; iron was unknown. Spinning and the weaving of cotton and wool were practiced by this civilization, barley and wheat were grown, and there was a fairly advanced urban culture. The relationship of these peoples to the Dravidians has not been established.

The appearance in the early 2nd millenium B.C. of the Aryan peoples marked a turning point in the history of India, as in other lands such as Persia, Greece and Italy. They entered India from the northwest, apparently in several waves of immigration, pushed the Dravidians to the east and south, and gathered in some strength between the Indus and the Jumna rivers. From this region, they spread themselves more thinly over the rest of India, and then, about the beginning of the Christian Era, undertook the colonization of lands across the sea in Indonesia and Indochina.

Vedic Times

The Rig-Veda, compiled in about 1500 B.C. by collecting much older hymns composed at different times and places, is an important literary monument to the Aryan settlers in the Punjab. It shows them organized in various tribes under elected kings who acted as guardians, priests and war leaders. The kings united at times against the black-skinned indigenes, but were by no means free from differences among themselves. Aryan society retained tradces of its ancient pastoral character; women occupied a high position in the family and even composed some of the beautiful hymns. The Aryans knew the uses of most metals, lived in villages and towns, fortified wherever necessary against enemies, ate beef and drank the intoxicating juice of the soma, which they offered sacrificially to their gods. At first they migrated in whole communities from one river valley to another, keeping their tribal and family organization free from any large admixture of the pre-Aryan inhabitants. As the area of Aryanization extended, a really mixed society and culture developed. In the south, the bulk of the population remained unchanged except for their acceptance of the new culture brought to them by Aryan adventurers and sages who came to trade and found asramas, or hermitages. While all the culture of North India and Maratha in the western Deccan are derived from the Aryans, the Tamil, Telugu, Kannada and Malayalam peoples retain their Dravidian character, even though largely influenced in various ways by Sanskrit literature and tradition.

Later Vedic Period

The progress of the fusion of the Aryan and pre-Aryan peoples and the emergence of an Indian or Hindu culture are seen clearly in the literature, still religious in its nature, of the epoch after the Rig-Veda. Relatively large kingdoms took the place of tribal states, and city life developed. Royal power grew and the importance of the popular assembly waned. Villages organizaed themselves, each under its own headman, and the rudiments of a local administration appeared. Women’s position was slightly lowered, and sons came to be preferred to daughters. There was progress in agriculture and handicrafts, with iron and silver coming into more common use. The division of the people into hereditary castes had begun, although as yet there were only four main groups or varna, and not the numberless subgroups that developed in the course of succeeding centuries. The color bar undoubtedly had something to do with the origin of this caste system, but for the most part it was a deliberate attempt to secure social integration among different sections of the population without prejudice to their varying habits, customs and outlook.

In religion, the cult of sacrifice became much more elaborate and costly, and the priests who were the custodians of its complex technique, the Brahmins, gained in importance. A reaction followed, however, and reflection and philosophy gained the upper hand; meditation was exalted above ritual, and emphasis was laid on the quest for the ‘ultimate reality’ in preference to securing the pleasures of life in this or the other world. It was the wake of this reaction, in the 6th century B.C., that the new faiths of Jainism and Buddhism arose, both in Magadha (modern Bihar).

Another notable development was in the sphere of popular religion, where a synthesis was effected between some Vedic deities and those that appeared to resemble them in the popular pantheon of the pre-Aryans. This process led to the emergence of Shiva and Vishnu, with Brahma as a distant third deity. The three gods, Trimurti, began to fill a large place in the affections of the people, and the many legends of their lives and deeds that fill the epics and the puranas undoubtedly embody much pre-Aryan lore. These legends became localized in different parts of India, and famous temples and shrines were erected everywhere. Pilgrimages to such centers and the rehearsal of the sacred legends connected with them have served through the ages as one of the most powerful bonds for uniting India. Temple worship and the doctrines of karma and transmigration came into vogue. The Ramayana of Valmiki, treating of the most popular story of Rama and his wife Sita; the kernel of the other great epic, Mahabharata, the story of the great war between the Kurus and the Pandus; and the core of the puranas (legendary history) must have been composed in this period also. Their continuous influence on the life and art of India can hardly be exaggerated.

Continued in The Early Iron Age

See Also,

History

The Chalcolithic Period