Vol. 2 - The Novice DM

The Novice DM is a follow up to Introducing Gameplay, which attempts to provide persons with no experience whatsoever in dungeon mastering with the basic skills needed to assume this role. Much of this volume assumes the reader is familiar with Volume 1, in spirit at least, as it begins with the assumption that the reader understands the player character sufficiently enough that rules applying thereto need not be repeated in this volume. This work is meant to take advantage of the still-existing Online Game License.

Contents

This volume is dedicated to those who have been volun-told to be dungeon masters, who find themselves without the least idea what to do, but are nevertheless game to dig in and try, come hell or high water. It is hoped that by keeping the role as simple as possible at the outset, such people can get a taste for DMing and thus take the next step toward a deeper, richer campaign.

Foreword

Assuming the role of dungeon master is beyond a doubt the weakest, least supported aspect of D&D, the truth of which is denied by none. While purported to be a position with all this grandiose power and prestige, it is far more associated with an individual wallowing in a morass of "what the fuck do I do now" than it is with a position of privilege. Most persons who try to take the game's helm soon find themselves unable to obtain any really useful advice, while being met with outlandish expectations from players who would never think of taking their turn. This is not to say that being a DM is thankless — it isn't to be honest, if one survives. Even a bad DM can count on receiving much appreciation from the players. But because the responsibilty is simply too high for those who have trouble with the role, a small bit of praise is rarely enough to keep going. The battlefields of the game, it is sad to say, are not filled with the enemies of virtue, but with strivers that failed.

The goal here, as it has always been, is to take someone with no experience in running the game and provide context for them fulfilling the role in simple, straightforward language, without assuming they already know something that has not yet been explained. For example, while D&D may seem like an imaginative or a mental activity, being a DM is a physical strain as well, as the mind of the DM is forced to engage with others and with the game's material at a high, unrelenting pace. All those neurons firing and all the stress of managing a group of people saps energy in just the same way as going on a run or performing hard labour. As a user of energy, the human brain is a hog... and dungeon mastering D&D will push that organ to its extreme, especially for those who are unused to the practice.

If the reader is like most novices, then the chances are you have never been the centre of attention for a group of people for more than ten or twenty minutes at a time. Stepping into the role of DM demands that you be the centre of attention for two, maybe three hours, to begin with. Preparing yourself mentally and physically for this is no different than deciding you're going to train to run the marathon, or take up racket-ball or kayaking. It's never said, but your diet, your beverage, and especially the comfort of the space you play in all must be designed and set up with the mindset of someone who is readying themselves for a wedding, or to give a speech in front of one's colleagues at an amphitheatre. This may, in some degree, overshoot what's asked of you, but that excess zeal only increases the chance that you'll have a comfortable, easy night of DMing, rather than one where you're clumsily staggering around, praying that it ends soon.

There are no books for novices that want to dungeon master that takes this stance. My own book on the subject was expressly written for those who already knew how to DM, who only wanted to do it better. It's a different world writing for a first-timer, and from the position that no phrase or encouragement can be used that employs an undefined abstraction that only someone who is already a DM might understand. Novices don't know how to "set the tone" or "build tension" or even "run a fun game with less prep." We can't begin by saying that the reader needs to "manage the scene" or "tell the players what they can see," because these depend on skill sets the novice doesn't have yet. We might as well be telling them to fly. And this is why instruction books about DMing always fail. Because, in reality, the famous DMs themselves cannot explain how they do what they do.

The first error that's made is to assume the novice DM has any capability at all of managing the player's expectations — which, frankly, is utter nonsense. The reader knows as well as I do that you have no idea what those expectations are, much less how to manage them. You may have, as a player, have had expectations of your own, but it's impossible right now for you to conceive of how the DM managed or did not manage your expectations, so how are you going to manage anyone else's? The answer is you can't, and so you won't, until you know a lot more about the game than you do now. So let's take everything about managing expectations right off the table.

And because this ideal of "the DM controlling expectations" is so pervasive, corroding every discourse a novice has to face when stepping into the chair, let's make your first act as a dungeon master be this: look at your companions and tell them, point blank, "This isn't going to be about making this a thrilling experience for you. This is going to be about my learning how to dungeon master, and your being patient with me." Right there, saying this, you should be able to relax. You're saying, "I'm willing to be the dungeon master here, but only under the conditions I can live by." This part doesn't need to be said, it's implied, as is the follow-up, "And if you don't like it, I can get up right now and do something else."

What a novice generally doesn't realise, and what this says, is that the decision making power is and always will be in the hands of the dungeon master, because we can get up and leave at will. Our investment is entirely conditional. The players are permitted to play, on our authority... and it is this implied authority, which should never be stated aloud between the DM and the players, that grants the DM the legitimacy to provide answers, to set boundaries, to arbitrate the rules and to be the last word on any subject. All these things exist because we have the power to stop. This need not be something we must dwell on further, but the fact of it grants you, the novice, the TIME to learn the game while you're running it. Because, realistically, you must learn it at your pace. You cannot learn it at the pace others expect of you — if you try, you'll fail.

Now, what kind of game can a novice actually run? Well, obviously, not a game that relies upon a lot of invention. Certainly not a game where ongoing tension, plot twists, and clever rhetoric must be invented out of the blue by someone who is a master at storytelling. You're not there yet. None of that was ever a part of AD&D anyway, which is the game this series is teaching how to play. No, the novice is only ready to play one basic game: pick monsters from the book, put them in a place, tell the readers their lives are in danger and then fight it out. For that, you'll need to understand the combat system, where this book is going to begin. You'll need to know what monster to pick — again, this is part of this book's contents. You'll need to know how much treasure to give, and how to lead the players back to town so they can buy things. We'll cover all this.

The premise may not be thrilling for the players, but let's not get ahead of ourselves. A cook on their first day is not expected to "run the kitchen"... so don't expect yourself to "run all of D&D" right out of the gate.

If the players don't like this, if they complain and demand more, then say nothing, stand up from your seat and begin to leave the room. Don't quit, don't even say you're going to. If the players try to stop you, then just make the excuse that you're getting a drink. That you'll be right back. That they should talk among themselves. If they're going to accept you as a DM, they'll recognise that you're not under an obligation for them that you don't have for yourself. To repeat: you are the DM. You are the one in charge. They may not know this, but if nothing else will send the message, you going "on strike" for five minutes will tell them more clearly than any words you might think to say.

The Combat System

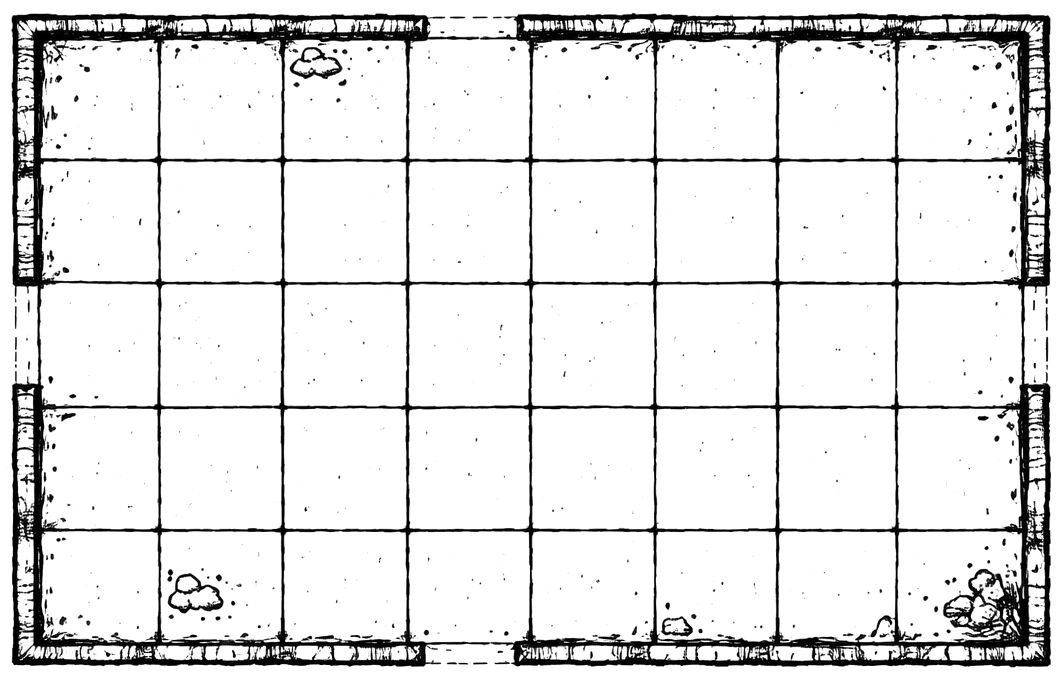

The Dungeon Masters Guide (DMG) of AD&D advises that new dungeon masters should take small steps at the start. It recommends that the game setting should be kept at a size commensurate with the needs of the participants, this including most of all the dungeon master. I so agree — which is why I believe that the entire setting a novice should start with is the map shown on the right. It is a room with four exits. As shown, it can be seen that the room is eight squares by five; each square is 5 ft. square, so that makes our setting a total of 40 by 25 ft. This is more than sufficient for a novice learning to run the game.

Imagine, if you will, that the four openings each have a door that closes them off. Now count the number of player characters against the number of squares — there are plenty of squares for the players to stand in. Each should pick one square for themselves, wherever they wish. Tell your players, "This is everything you know about the game world... just this room. You don't know how you got here, you don't know anything about your lives, you only know this room, and you've been here all of two minutes. To learn about the rest of world, you'll need to get out of this room — but it's not a puzzle. In a moment, one of the doors is going to open and things will come through it; when you defeat those things, you will have a means to escape the room."

This plan simplifies everything for us at once. First, it avoids the early session drift of players who can't decide what their characters should do, which is very hard on a DM who doesn't know how to manage the game. Secondly, it suspends any need for the new DM to provide background, context, justification, an adventure "hook" — designed to tempt the players into an action — or anything else that normally causes panic. We've already told the players to accept that we're learning to DM, so that justifies the entrapment. Finally, lo and behold, the situation is tense. We've achieved tension and so far, we've done nothing. No monologue, no plot twist, no “tone setting,” no acting. It’s the simplest demonstration possible that tension is a structural property of the situation, not a performance delivered by the DM.

While the players puzzle out which door things come through, let's decide what. You should have insisted that the players roll up 1st level characters, as is expected by AD&D. This limits the possible actions the players can take to fighting, a few spells and the bare minimum of equipment benefits. The DMG thoughtfully includes a list of opponents specifically suitable for a party of "1st levels" (on page 175) — and from these, we can pick the "goblin"... a diminuative humanoid with 1-6 h.p., which by the reckoning of the DMG, appears in numbers of 5-15 (2d6+3). Let's make this easy — assume 1 goblin per player character, or a minimum of 5 goblins even if there are only two players.

Goblins are a good start because they have no special abilities, they're mechanically simple to manage, they can be perceived as having one motive — kill or die — and we can set their h.p. in a manner that allows us to balance the enemy for the party. If there are five party members, don't roll for the goblins' h.p., assign them all 4 h.p. Then, add or subtract 1 h.p. per character below five, or add 1 h.p. per character above five. If there are six player characters, all the goblins have 5 h.p. If there are four player characters, all the goblins have 3.

Remember two things: to start, we want the players to all live. There's a lot more setting outside the door, which they all deserve to see. Second, as a novice, concentrate on the goal of learning the system. Later we can mess around with individually rolling the goblin's hit points or giving them each agendas, but for now, McGoblin will do nicely. And the players won't care. Don't try to be clever, immersive or impressive. As this is your first game ever, your hands are full with managing initiative, movement, attack rolls, damage and spells. Keep it simple.

Now, before going through the early combat procedure, let's handle placement.