Abbey

abbeys are facilities composed of groups of Christian Catholic monastic buildings, typically arranged around a central church, forming a self-contained complex that supports a population devoted to religious life. These structures include dormitories, refectories, cloisters, chapels and workspaces, all functioning together to provide for the physical, spiritual and communal needs of the monastic order. Abbeys serve as the principal training ground for the monk character class, offering a structured environment where discipline, physical conditioning and theological study are pursued in equal measure. In Alexis's game world, monks of the west are trained to the same level of martial and defensive prowess as those from eastern traditions, making no distinction between the origins of the monastic tradition when it comes to their effectiveness in combat.

Contents

Abbeys are self-sufficient and isolated from the general world, often denying the entry of outsiders altogether in keeping with their strict adherence to spiritual focus and communal order. The internal layout of each abbey varied according to the specific rules and practices of the monastic order it housed, resulting in distinct architectural features and plan arrangements that reflected the priorities of discipline, work and worship. No distinction is made in the game world regarding whether an abbey is occupied by males, females or both, as all serve the same purpose as centres of religious life and monastic training.

Origins

From the early days of Christianity, beginning in Egypt, groups of devout individuals gathered around the dwellings of persons esteemed for their exceptional holiness, who lived as religious sectarians or prophets. These followers would construct their own dwellings in the same village, choosing to submit themselves to the rigorous discipline and spiritual practices of the central figure. Over time, these loose associations evolved into structured religious communities, committing themselves to the pursuit of a meaningful spiritual mission, such as caring for pilgrims or offering shelter and guidance — and in doing so, becoming destinations for pilgrimage and refuge themselves. The first European monastic order, the Benedictines, experienced swift expansion in Italy during the 6th century, and by the 8th century, their abbeys were widely established throughout western Europe.

By the beginning of the 12th century, many abbeys had accumulated significant wealth and influence. They oversaw vast landed estates and constructed richly adorned churches, which were soon complemented by a growing collection of monastic buildings. For extended periods, the arts were cultivated almost entirely within these religious communities, as members of the monastic orders became leading patrons of art, while also asserting influence in matters of religious doctrine and civil governance.

Architectural Development

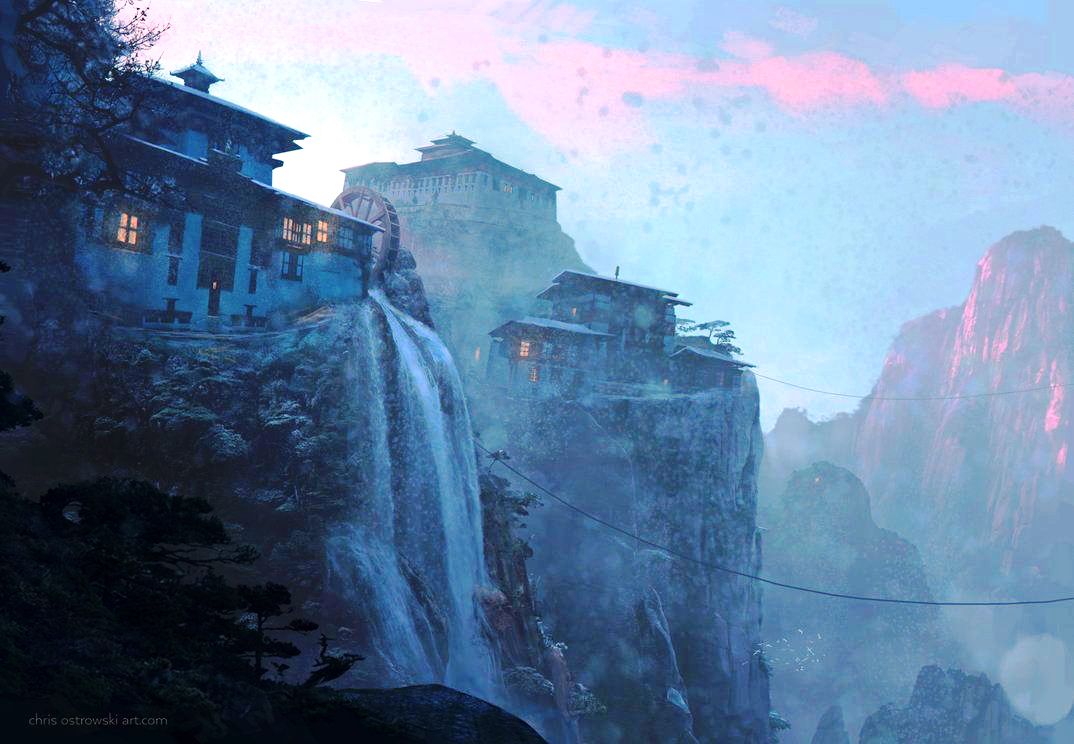

While monastic institutions were taking shape during the 6th century in Italy, the architectural organisation of these communities did not immediately take on a consistent or recognisable form. Yet, due to the instability and insecurity of the Dark Ages, it became necessary for these institutions to contain within their walls everything required to sustain the chapter without relying on external support. The abbey thus emerged as a self-contained and fortified religious city, incorporating gardens, mills, stables, workshops and other domestic facilities essential to its independent economy.

Because these religious communities distinguished between lay brothers and monks, the design and layout of abbeys reflected the need for internal segregation. As the monastic system matured, abbeys grew into complex, deliberately planned arrangements, with monks' houses, infirmaries, libraries, chapter houses and other necessary structures all carefully grouped about the cloister, each element thoughtfully positioned in relation to the central church. The abbot or abbess occupied a separate dwelling, and beyond the abbey walls lay the extensive estates held by the order.

The general architectural style of early monasteries was Romanesque, marked by solid forms and rounded arches, but as the Gothic style emerged and gained popularity, the monastic institutions readily adopted the new aesthetic. Over the centuries, many abbeys were reconstructed or modified, leaving behind limited traces of their earlier forms. A significant number of ruined abbeys display Gothic features, though structures like Fountains Abbey, which was abandoned in 1539, still carry the weight and form of the Romanesque. Monastic architecture did not end with the medieval period; later examples such as the Certosa near Pavia and the Escorial, located thirty miles from Madrid, demonstrate how the tradition continued into the Renaissance with increasingly elaborate expression.

Benedictine Abbeys

Monte Cassino, established in 529, is the oldest abbey in Europe, though its history has been repeatedly interrupted by conflict and destruction. It was first abandoned after the Lombard attack in 570, and again by the Saracens in 718, necessitating multiple reconstructions over the centuries. The abbey reached its peak in the 11th and 12th centuries, during which it accumulated vast secular holdings and defended these lands with an extensive network of fortified castles. Its influence began to wane in the 13th century. The buildings were destroyed by an earthquake in 1349, and after 1454, the abbey's leadership was placed in the hands of a patron rather than the monastic community itself. By 1504, Monte Cassino had become subordinate to the abbey of Santa Giustina in Padua.

St. Gall in Switzerland, erected around 820, offers a more comprehensive glimpse into the structure and operation of a monastic community. Its double-ended church is surrounded by an orderly complex of buildings that include workshops, mills, a kiln, farm buildings, a cemetery, kitchens, bakehouse, brewhouse and a cloister, in addition to dormitories, refectory, scriptorium, infirmary, school and guesthouses. The plan conforms to the Benedictine rule that the abbey must provide for every aspect of monastic life within its own grounds, eliminating the need for monks to seek necessities outside. As a result, St. Gall appears more like a small, self-contained medieval town, its buildings separated by streets and gardens.

Westminster Abbey, founded by St. Dunstan in the 10th century, exhibits marked French influence in both its design and proportions. The eastern extension of the choir, to which the chapel of Henry VII was later appended, remains unique in Great Britain. The nave is notable for being the tallest in England. Located at the heart of London, Westminster Abbey includes cloisters, a refectory, chapter house, chapel and cellars within its complex.

Cluny was a major centre of Benedictine monasticism, founded in 910 in eastern France. At its height, it was the largest monastic establishment in Europe, with a network of subordinate houses and considerable religious authority. Its prominence diminished in the wake of the Cistercian reforms, which favoured austerity over grandeur, and again during the Papal Schism from 1378 to 1409. Despite its decline, the Cluniac abbey retained considerable influence throughout Burgundy and with the French crown.

Cistercian Abbeys

Fossanuova, located in Italy and dating from 1135, reflects the austere principles of the Cistercians, a reformed branch of the Benedictines who emphasised simplicity in both their lifestyle and architectural expression. The abbey's Gothic church is cruciform and square-ended, stripped of ornament and built for function. On one side of the church lies the cloister, alongside which are the refectory and chapter house; on the opposite side, the cemetery occupies a reserved space. Other essential structures, including the hospital, guesthouse, farm buildings and gardens, are distributed informally within a walled enclosure, maintaining the order's ideal of self-sufficient seclusion.

Clairvaux in France shares a similar arrangement, though the surrounding rugged terrain made for a less formally structured layout. Founded in 1115, the abbey was fortified with a high enclosing wall, punctuated at intervals by watchtowers and defensive positions. A moat, diverted from nearby tributaries, runs partially or entirely around the complex depending on seasonal water levels. This same water source was used to irrigate gardens and supply sanitation within the abbey. Clairvaux reflects the Cistercian ideal of settling in harsh, remote landscapes to support an ascetic life. Decorative features typical of the Gothic period, such as towers, stained glass and exterior embellishment, were forbidden by the order's rule.

Fountains Abbey, an important Cistercian foundation established in 1132 on the River Skell in England, demonstrates a departure from the strict simplicity seen in other houses of the order. The abbey's design became more elaborate over time. On the west side of the cloister, a long range of vaulted rooms extends across the Skell, serving as cellars and storehouses, with dormitories positioned above. The abbot's house, situated at the far eastern end of the complex, was one of the most extensive and ornate in England, with parts of the structure built on arches spanning the river. The house's great hall measured an impressive 170 feet in length and 70 feet in width. As previously mentioned, Fountains Abbey was abandoned and, by 1650, stood as a ruin in North Yorkshire.

Carthusian Order

Founded about 1084 by St. Bruno, the Carthusian Order established its principal abbey at Chartreuse, a remote and barren site near Grenoble in France. The order's strict discipline, built around solitude and silence, required that each monk live in a separate cell, leading to a distinctive approach to monastic layout unlike that of any other religious order. The plan of La Grande Chartreuse presents a nearly symmetrical design enclosed by heavy walls, with watch towers reinforcing each corner. The church occupies the central axis of the compound, surrounded by the usual communal structures necessary for shared religious life. Behind the church lies the main cloister and the cemetery, both arranged in seclusion, and ringed by the individual monk cells.

At the front of the abbey, near the entrance, are placed the guest quarters, the prior's residence, barns, granaries, bakehouse and workshops, forming an outer court that separates visitors and labourers from the inner life of the monks. Each cell contains three rooms: a sitting room with a hearth for warmth in winter, a sleeping chamber furnished with bed, table, bench and bookcase, and a small private closet. Each monk also tends a private garden, attached directly to his cell. Food is passed through a wicket that prevents any interaction, ensuring silence is maintained, and the entire structure is designed to insulate the monk from any noise or distraction that might disturb his contemplative life. The prior has the ability to inspect the monks' gardens without being seen, preserving both order and solitude. This overall arrangement is consistent across all Carthusian monasteries in western Europe.

Other Orders

The Dominicans, Franciscans, Carmelites and other orders likewise developed architectural arrangements suited to their particular functions, though these were generally less distinctive than those of the previously mentioned communities. As preaching friars, they required larger churches to accommodate congregations, which influenced the proportions and layout of their religious houses. Nevertheless, when not constrained by environmental or urban limitations, these orders also established monasteries featuring elaborate constructions arranged around a central cloister, following many of the same planning principles common to monastic life.

See Rural (range)